29. Per Bylund on the Critical Importance of Executional Excellence and How To Achieve It

Have you heard of the knowing-doing gap? Accumulating unique knowledge – expertise, processes, experience, skills, recipes, qualifications etc – is important, as we always emphasize at Economics For Entrepreneurs. In business, that’s half the story. The second part is effective action, judged by results. Knowing what to do translated into actually doing it. Becoming not just a learning organization but a doing organization.

Dr. Per Bylund framed it this way: having a great idea for a business is not the crucial element for success. It’s whether you can pull off the idea in implementation. That’s what investors and customers are looking for – not the idea, but executing the idea.

Key Takeaways & Actionable Insights

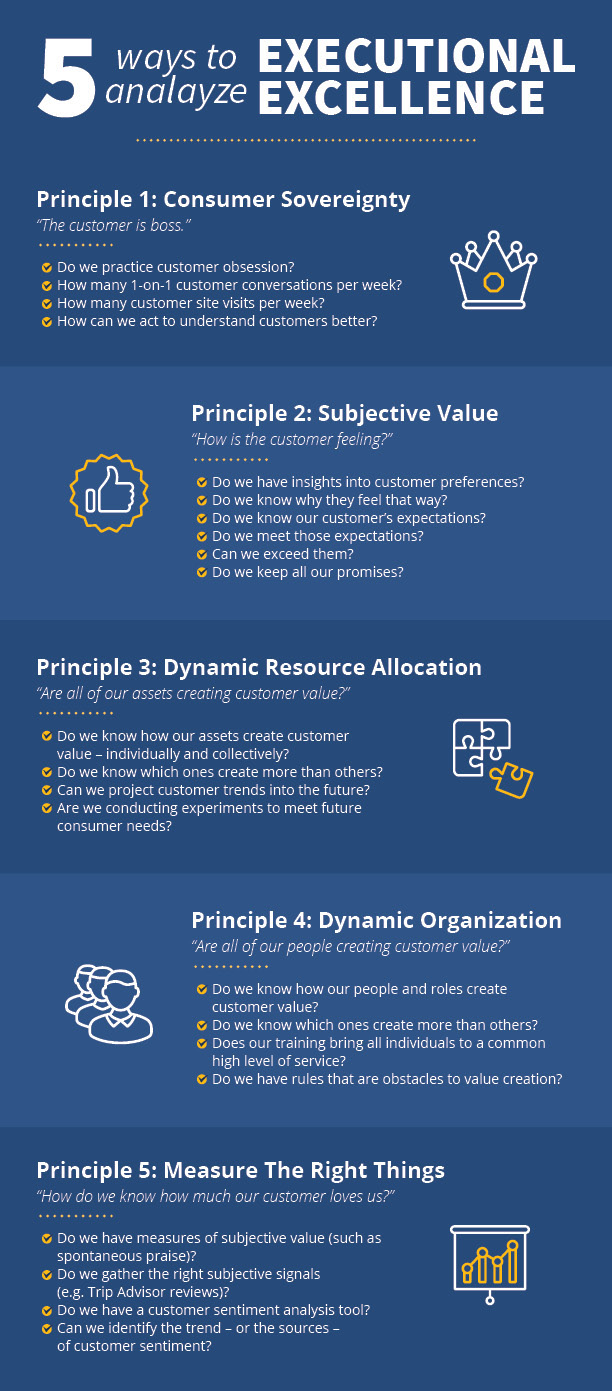

Dr. Bylund guides us with 5 Austrian action principles.

Principle 1: Consumer sovereignty. The consumer is boss and decides whether a business is executing well, i.e. to customers’ satisfaction. The only purpose of a business is to make and keep customers. Amazon calls this customer obsession – everything starts and ends with the customer, and the customer is central to every decision, in every resource allocation, and is invisibly present in every meeting and presentation. Does your company act this way? Are you certain you know and understand your customers’ needs and preferences, and their hopes and dreams? Are you deeply immersed in customer knowledge? Do you talk one-on-one with customers as often as possible? Do you go out to the building sites where they use your equipment, or to the offices where they use your software, or to the homes where they consume your food and beverage products? The consumer culture is exemplified by anthropology – getting out there with your users. Jeff Bezos observes that consumer-obsessed companies act differently. What actions are you taking to observe, understand and serve individual customers better?

Principle 2: Subjective Value. The consumer or customer you are getting close to by implementing Principle 1 is the decision-maker on whether or not your firm is providing value. Their decision is subjective – it’s entirely theirs, entirely emotional, entirely about their perception. Do you know what factors are the most persuasive and influential in creating a positive perception? We discussed a case study of premium vodka. The basic liquid is to a great extent an undifferentiated commodity. Differentiation comes from the varied subjective experience a consumer can feel in ordering and consuming and sharing a brand of vodka. How much of that perception is affected by the bottle shape design and the label design? How much by the social prestige of the location where the brand is served? How much by the consumer’s perception of the merit of the people who drink this brand? It’s hard to know but necessary to find out.

One route to implementation success in business is to manage expectations. Find out what customers expect, then make a promise to meet those expectations and keep your promise. So often in business, promises are made but not kept. That means you created an expectation, then did not meet it. You should make sure to do the opposite.

Principle 3: Dynamic Resource Allocation. The Austrian principle is that the firm’s capital and resources are, at all times, a reflection of the market and of customer preferences. What does that mean and how can a firm activate this principle? In practice it means two things. First, do not lock in to any asset or resource that is difficult to change or adjust on short notice. Stay flexible at all times. Second, make sure that you are collecting market signals – data – that tell you what you need to know about customer preferences today (not yesterday) and will provide you with insights into where they might shift tomorrow. Based on those insights, conduct experiments and tests that can be quickly scaled up when they show results, and quickly shut down when they don’t. If you find yourself responding to changes in customer preferences – or, even worse, changes in competitors’ behavior that seem to be more responsive to customers than your own – it’s too late. Get comfortable with continuous change.

Principle 4: Dynamic organization. How can you identify and eliminate all the barriers to your team’s empowerment to serve the customer in the way the customer prefers? Often, the barriers can be found in rules. In customer service, for example, there may be rules about the level of decision-making delegated to a customer representative, or even the amount of time a representative can spend on the phone with a customer. Examine all your rules, standardized protocols and bureaucratic structures. For each one, ask: does this contribute to the satisfaction of the customer? Does it produce customer value? Or is it to cut cost and minimize risk? Cutting costs will never add value. To be great at implementation, examine all practices to make sure they are value-creating and not value-consuming. Who decides? Your customer.

Perhaps you have employees who are not value-creating. You can’t afford them.

Principle 5: Measuring The Right Things. With metrics, most business advice is to be objective and numeric. You are advised to measure sales, profits, distribution, etc., and take surveys of customer satisfaction expressed as numbers on a scale or percentages compared to a norm. For great execution, it is far more important to measure subjective value, and to shed light on what the firm is doing right in the creation of consumer value and where it is falling short. This is a challenge, but not an impossible one. There are places to look, such as sources of spontaneous praise. Your firm’s Trip Advisor comments from recent visitors, for example, if natural, honest and spontaneous, can be great indicators for you. The same goes for other spontaneous commentary channels. Commit to conducting a minimum number of in-person one-on-one customer conversations every week. Summarize them. Conduct sentiment analysis. Try to develop data on the direction that sentiment is trending – modern tools can do this via language analysis and emotional content analysis. Commit your firm to becoming the best at monitoring, projecting and analyzing subjective customer perceptions.

Do you have any experience of measuring subjective value creation? What has worked for you?

DOWNLOAD

Download Our 5 Ways To Analyze Executional Excellence PDF (129 KB)