174. Sterling Hawkins: Discomfort Is Your Most Valuable Feedback Loop

Negative feedback loops are the ultimate source of value. Mises called it “uneasiness and the image of a more satisfactory state”. Bill Gates said that “Your most unhappy customers are your greatest source of learning”. Negative feedback loops give us the opportunity to improve our service delivery capacity, and the value proposition behind it. Sterling Hawkins has identified the ultimate feedback loop for personal performance. He calls it discomfort. We should seek discomfort, analyze it, understand it, and utilize it as an ultimate tool for improvement. His book is titled Hunting Discomfort (Mises.org/E4B_174_Book) and we talk to him about it on the Economics For Business podcast.

Key Takeaways and Actionable Insights

Discomfort is a feedback system.

There will always be physical, mental, emotional, or even spiritual discomfort in our lives. It’s necessary and useful. It signals to us how we are interacting with our environment. It keeps us oriented. Sterling’s case is that we shouldn’t try to avoid it, we should embrace it – he recommends that we actively practice hunting discomfort. Once we find it and embrace it we work our way through it, and the result is personal growth. We get better.

First, face reality.

The first discomfort Sterling outlines is facing reality. In business, we often say that it’s a great challenge to align the firm’s internal assessment of reality with what is actually going on in the external environment, especially in times of rapid change. We may just not see reality accurately. Our product may not be as well-liked by customers as our research tells us it is.

We can’t change reality, but we can change how we see it. We can change our belief structure. One way is to run many experiments where we can objectively and empirically measure results, and expand on what works and discard what doesn’t. We might find some things that work that we didn’t believe could. And we might find that we thought worked simply does not. Both represent valuable learning and provide us with a reality we can grasp.

Eliminate self-doubt.

Self-doubt is mentally wrestling with questions and beliefs and insecurities. It’s the world of “I might” rather than “I will”. Sterling’s advice is that self-doubt can be a gift. It indicates an unwillingness or inability to commit. And yet commitment is often associated with entrepreneurial success. It’s part of what Professor Peter Klein calls entrepreneurial judgment: the capacity to choose which action to take and to follow through with it.

Choose your commitment as wisely as you can – which includes choosing those actions not to take. Sterling’s metaphor is Get A Tattoo. It’s an irreversible commitment everyone can see.

Some people find discomfort in exposure.

If you commit, you might feel more exposure than you’re comfortable with. You might have to raise money, when it’s not your skill. You may have to make a presentation about which you’re not feeling 100& comfortable. You might be the only one expressing disagreement in a meeting full of groupthinkers.

Sterling’s recipe is to assemble a support group — he calls it your street gang. They’re supporters, subject matter experts, mentors. You’ll make your commitment to them, and they in turn will give you honest feedback, trust, and loyalty. You’ll still be committed but you won’t feel so exposed.

We take on greater and greater challenges — and that’s uncomfortable.

As businesses take shape and grow, the challenges only get bigger. We might get to the point where we want to avoid some of the big challenges. But that’s the wrong viewpoint. The alternative is to turn challenges into an opportunity to find new ways to utilize our resources — to use them as a portal to advance from the status quo to a new reality. The method is reframing. What if you tried the opposite of the status quo solution? What if you looked at the challenge through someone else’s eyes, using their mental model rather than your own – what would they do? What if you change the assumptions about the way you’re addressing the challenge? There are many ways to reframe challenges, and reframing can release you and give you new energy.

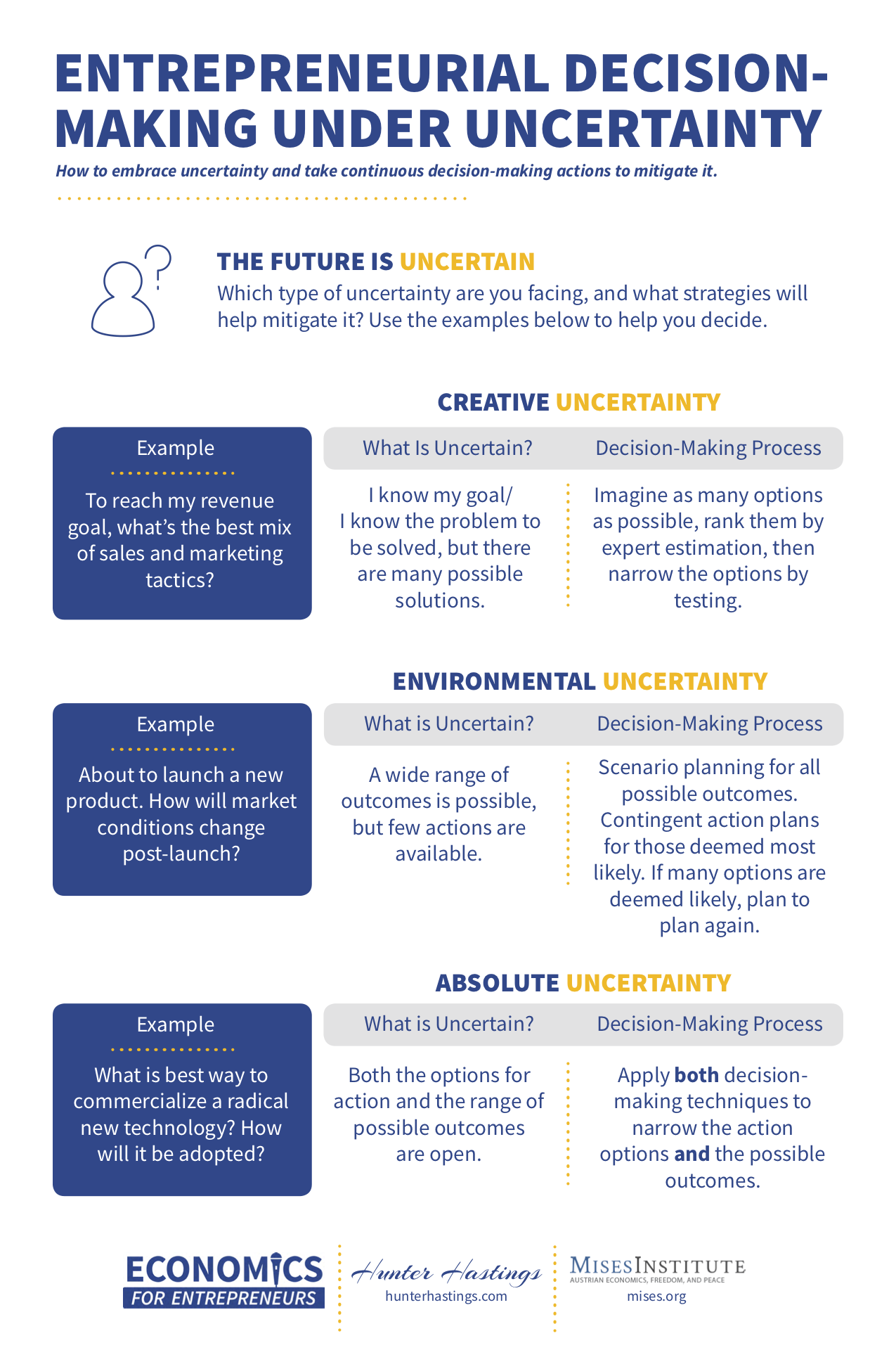

The greatest discomfort is uncertainty.

Economists talk endlessly about uncertainty in business. It’s a consequence of the unknowable future. But you own your own uncertainty — for entrepreneurs, it’s a feeling, not an economic concept. It’s subjective. We’re not only uncertain about outcomes, but about resources, about financing, about our capacity, about our partners. Uncertainty is multi-dimensional. It’s also guaranteed — we can’t avoid it.

Economists, therefore, say that entrepreneurs bear uncertainty. It’s what they do. It comes with the job. Sterling’s word is surrender: don’t fight or fear uncertainty, but accept it willingly as a cost. Give up resistance. Get into your discomfort zone. Entrepreneurs need to be doing hard things most of the time, however uncomfortable that might be.

Additional Resources

Hunting Discomfort. How To Get Breakthrough Results In Life And Business No Matter What by Sterling Hawkins: Mises.org/E4B_174_Book

Visit SterlingHawkins.com