21. Peter Klein on Transaction Costs

Are you transaction cost-savvy? Peter Klein explains why it’s important.

We emphasize profitable value creation as the role of the entrepreneur. Managing costs can contribute to profitability – but there are some costs that are not easy to calculate and not even that easy to identify in some cases. They are not captured by traditional cost accounting. Economists call them transaction costs. They are the costs of acquiring, assembling, monitoring and managing and, in some cases, discarding or re-purposing the resources and assets your firm utilizes to produce output. They are not production costs per se; they are not value creation costs. They’re administrative and managerial costs.

Peter Klein explains:

Show Notes

Think of any transaction, like buying a cup of coffee at a Starbucks store. Now think of all the economic costs of that transaction above and beyond the actual dollars you hand over to the barista.

There’s the cost of traveling to the store, in both time and money (gasoline if you drive) and wear and tear on your vehicle. There is time spent on studying the menu, explaining your choice and waiting for delivery – and time is the entrepreneur’s most precious scarce resource.

Now apply that same thinking to the acquisition of any resource you want to bring into the firm to support your business model. There are many transaction costs in addition to the purchase price.

There is the time taken to research features and attributes, and comparative pricing. There may be negotiation or haggling with the vendor. There may be legal costs in a contracting process. There may be integration costs to fit the new resource into your production chain. If you’re buying from a wholesaler, there are issues of timely delivery and accurate order fulfillment you must monitor and manage. If the new resource is an employee you are hiring, there are advertising, interviewing and negotiation costs, as well as the benefits package that accompanies the salary agreement. All of these transaction costs, across the entirety of your business, add up to an amount that is pretty significant.

And, once you own the resource, transaction costs don’t disappear. They transform into monitoring and management costs.

Peter used the example of Walmart’s trucking fleet. Walmart owns many trucks and the drivers are employees. There are extensive monitoring costs associated with the ownership of these resources and the employment of the drivers and mechanics and service technicians. This group of costs can be characterized as the cost of confidence that you are getting the performance that you want out of the resource you own. In the case of Walmart’s truck fleet, these costs include monitoring the vehicles themselves (location, speed, downtime, tons hauled, gasoline used, etc), the drivers’ productivity, the maintenance burden, delivery accuracy and many more metrics. Walmart employs people and uses technology assets to implement all this monitoring, and those monitoring resources are not really creating value; they’re supervisory overhead.

Another kind of transaction cost arises when you decide you want to recombine, reshuffle or discard assets, or to use them in a new way.

In the entrepreneur’s uncertain business environment, it’s never certain that the asset you have acquired or the people you have hired are always going to be perfectly tuned to your business model. Circumstances change, and you want to make adjustments. Is the asset adjustable? Does the employee have exactly the skills you want for a new process or method? Will you be able to reprogram the asset or redirect the employee to a new job function? In many cases, you might have need of the legal system for a revised contract (legal costs are transaction costs), or there may be regulations preventing you from closing a plant or laying off workers. Any time you are constrained from making the adjustments you want at the speed you prefer, you are facing transaction costs. Could you have anticipated the situation when you first contracted for the resource or first hired the worker? Probably not – but trying to do so would be a transaction cost in itself!

Often, the issues raised by the problems of transaction costs are characterized as “make versus buy” decisions. Or rent versus own. Or in-house versus outsource.

It seems that there is a tendency today towards organizational models that are asset-lite, with a lot of the control that the firm seeks to exert over resources being exercised through renting or outsourcing, or by utilizing independent contractors rather than directly hiring employees. (Actually, Peter disputes this, suggesting that many such business models get a lot of publicity but there is no general tendency across multiple business sectors.) Does a virtual organization chart or a network model compared to a hierarchical model always have lower transaction costs?

Not necessarily. Compare Amazon, which mostly utilizes FedEx and UPS and USPS to make deliveries. Amazon still has many of the monitoring costs that Walmart has – it’s just that they are monitoring an outside vendor. Yes, FedEx and UPS bring their own tracking systems and technologies, but Amazon can’t afford to let its vendors go un-monitored.

In fact, in-house transaction costs are declining at the same speed as outsourced transaction costs.

With the advent of software HR and CRM systems and other kinds of monitoring and management technologies, internal transaction costs are not as burdensome as they were in the past. It would be unwise to make the automatic assumption that in-house transaction costs are always higher than outsourced costs.

Actionable Insight

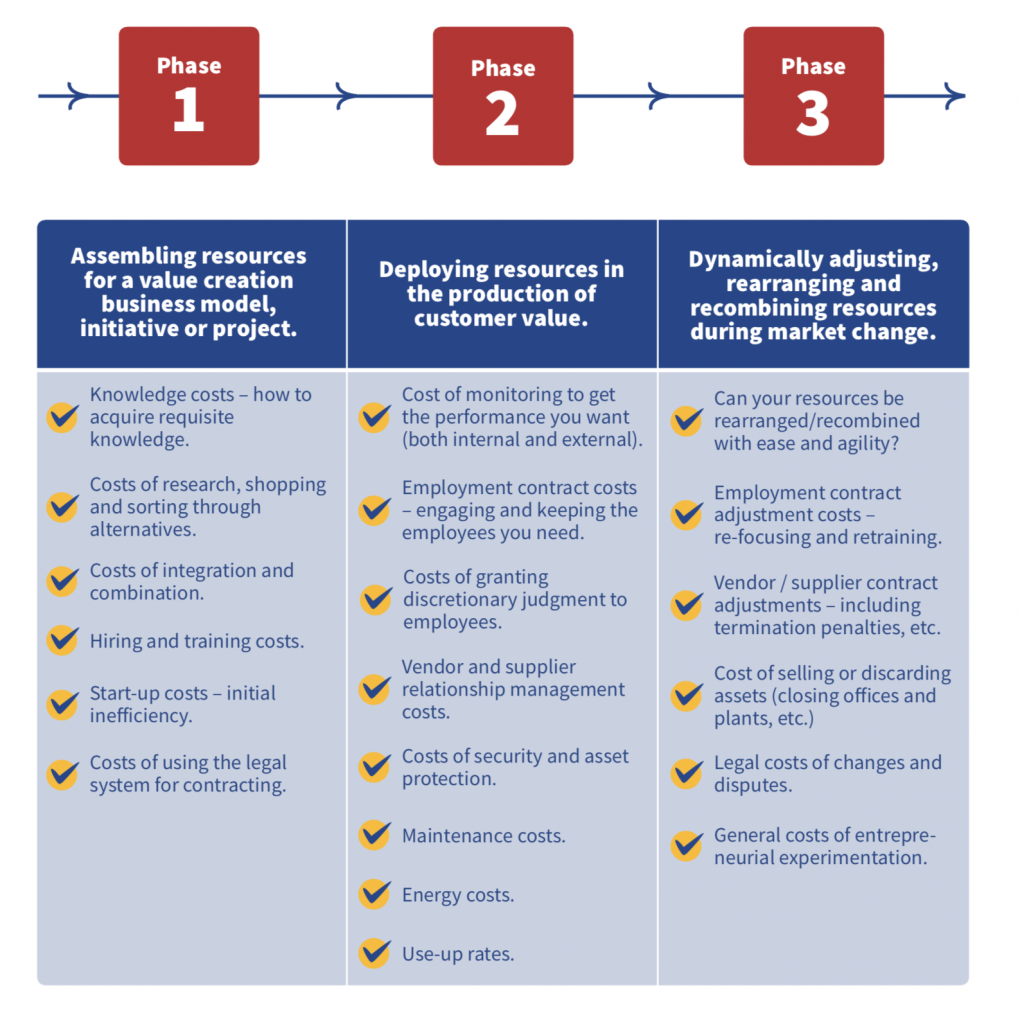

So what’s the answer for entrepreneurs? There’s no simple formula, just the admonition to be transaction cost savvy. In every situation where there are alternative scenarios, the savvy entrepreneur thinks through the transaction costs of each one, and makes a best estimate of the economic costs. He or she thinks about the present costs, the future ongoing monitoring costs, and the potential costs when there is a future adjustment to be made.

Always relate this economic calculation of transaction cost alternatives to the creation of customer value. What is the best alternative transactional mode or organizational mode to deliver value to the customer, today, tomorrow and a year from now? What is the cost of the resource control you need in order to deliver value, especially if customer preferences change and you want to change with them?

Download our transaction cost checklist to help you become transaction cost savvy.

Buy Peter Klein’s book Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgement on Amazon.

Here are extra links to information that Peter Klein mentioned in the podcast:

An article Peter wrote to commemorate Oliver Williamson’s Nobel Prize – he is the originator of “transaction cost economics,” which is closely related to today’s discussion topics, though not directly dealing with entrepreneurship.

A longer, more academic survey on transaction costs – may be a useful reference.

Also, listeners may enjoy the comments on this blog post.

DOWNLOAD

Download the 3 Phases of Entrepreneurial Transaction Costs PDF (101 KB)