28. Steve Phelan on Negotiation As A Core Capability For Entrepreneurial Success

Negotiation is a capability that entrepreneurs use almost all the time. It’s an area of entrepreneurial performance where an understanding and application of Austrian Economics can be very helpful.

Key Takeaways and Actionable Insights

It’s all Austrian! Negotiation skills represent one of the resources entrepreneurs must assemble and maintain. The value of any resource is subjectively determined, and so the price is never fixed, it’s subject to negotiation. Two people can have different subjective opinions about the value of a resource – and those opinions can change, e.g. during the course of a negotiation, when one agent changes the opinion of another.

Negotiation starts on Day 1 and never stops. Founders deciding to set up a company negotiate over who plays what role, who gets what share of the equity, and so on. From Day 1, the entrepreneur bargains for advantage, putting the best case forward at all times, and always thinking ahead to the next negotiation.

In Bargaining For Advantage (Revised Edition, 2018), Richard Shell lays out 6 principles of negotiation that Professor Steven Phelan, himself a teacher of negotiation strategies to entrepreneurs in business school, reviewed and illustrated with examples.

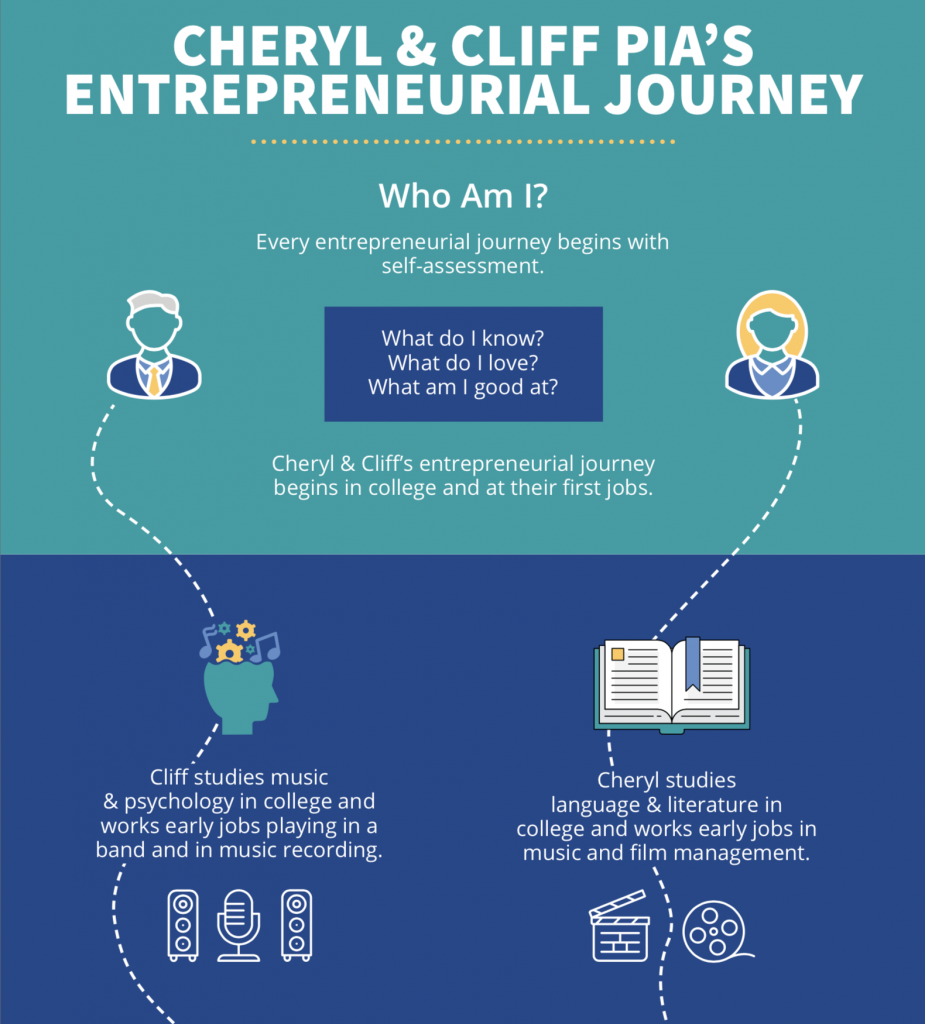

Subjectivism: Know Your Own Bargaining Style. The entrepreneurial journey starts from self-assessment: Who Am I? Some people are uncomfortable with negotiation, and sellers might take advantage by making only fixed offers. There is a competitive negotiation style and a co-operative negotiation style, and some points on the spectrum between them. (Most professional negotiators think of themselves as co-operative.) Don’t feel bad if you hate the confrontation of traditional negotiation. You don’t have to drive the hardest bargain. You can control the timeline for greater reflection. You can prepare yourself well to reduce your anxiety. Know yourself, accept your self-knowledge, and learn how to apply it for advantage.

Know your ends and select the best means. Ends-means analysis is fundamental to entrepreneurship, as it is to negotiation. Identify your own expectations, set your goals high, and be ambitious. Remember that a goal is not a fixed point – like a price to settle on. It’s complex and layered and can have a lot of non-monetary components. These are the elements you can vary to adjust the bargaining advantage in your favor, by using them as concessions, or trading them for a better deal. For example, you may be able to reach the price you want by providing seller financing.

Use external – and authoritative – standards and norms to help you. Norms can narrow the uncertainty in negotiation for both sides. For example, real estate agents use “comps” (recent sales prices of comparable homes in the local area) to narrow the range of possible prices in a transaction. Of course, there are multiple norms and standards that could be used – like price per square foot, or lot size, or views – and you should know them all, select your preference, and then argue persuasively in favor. Pick a standard that shows your offer in the best light.

Time preference – thinking long term. A negotiation might seem like the very definition of short-term: you want a good outcome now! But is this the last time you’ll negotiate with this party? Does your agreement in this situation potentially affect future negotiations? If you bargain a new hire down to the lowest compensation level, do you risk them leaving in the future and jeopardizing a team project? Think of the second order consequences and the lifetime of your business. It’s a mark of the good economist – and the good negotiator – to always think in the long term.

Use empathy as the planning basis of all negotiations. We’ve emphasized many times that the core skill of the entrepreneur is empathy – understanding the feelings of the other party, whether that’s a customer or a party to a negotiation. Why is the other party negotiating with you at all? What do they want – or need? Get to know them as people. Take them to dinner. Meet their family. Can you ethically meet their personal needs as well as their corporate needs? You can never eliminate all uncertainty, but deeply understanding the other party can go a long way towards doing so.

Find your leverage: the situational advantage to reach agreement on your terms. Of course, leverage in a negotiation can be positive or negative at the outset, depending on the situation. You should always look for ways to reduce the value of the other party’s alternatives (that’s their leverage) and increase the value of their own. Put scarcity on your side by having more than one bidder for what you are offering. Use time – leverage can change over time, especially if you can wait and the other party can not. One useful tool is BATNA – best alternative to a negotiated agreement. If you have more alternatives than the party on the other side of the table, that gives you leverage.

Use the six principles to prepare a strategy. Shell recommends that you make your opening position as aggressive as you can, and support it with the best norms and standards you can compile. That will put the other party in the position of having to find contrary logic as a counter – it’s called anchoring: your opening bid becomes the anchor for locating the range of negotiation. Never meet in the middle. Let the other party concede first. Shell refers to if-then thinking. If you’re called upon to make a concession, then you know exactly what counter-concession you are going to call for from the other party. Never concede voluntarily, always ask for a responding concession.

Have a specific negotiation plan in mind. Use the accompanying planning tool, adapted from Richard Shell’s book. Physically fill it out, use empathy, acknowledge uncertainty, gather as much information as you can, find your own norms and predict which ones the other party will use, find a good agent if you need one. Planning in advance will give you confidence and help you succeed, even if you don’t relish negotiating.

Use this 10-step planning guide to plan your next negotiation.

DOWNLOAD

Download Our 10-Step Negotiation Planning PDF (124 KB)