66. John Tamny On America’s Uniquely Productive Entrepreneurial Flywheel

The flywheel is a robust and powerful mechanism so long as restrictive regulation by government and failures of imagination by capitalists do not slow it down.

John Tamny speaks articulately with Hunter Hastings about the uniquely American entrepreneurial flywheel in Economics For Entrepreneurs podcast #66.

Key Takeaways and Actionable Insights

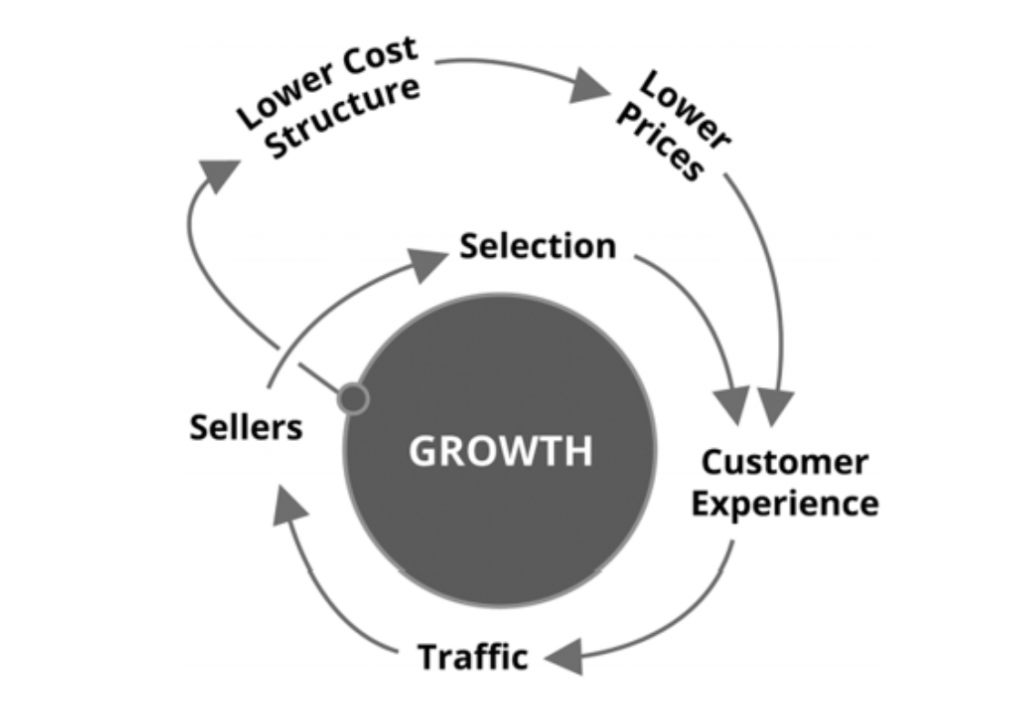

A growth business is what John Rossman, in episode #50, termed a flywheel. Using amazon.com as an example, he gave us this simple image.

The flywheel looks simple, but in reality it’s quite nuanced. Lower prices and a great customer experience will bring customers in, Bezos reasoned. High traffic will lead to higher sales numbers, which will draw in more third-party, commission-paying sellers. Each additional seller will allow Amazon to get more out of fixed costs like fulfillment centers and the servers needed to run the website. This greater efficiency will then enable it to lower prices further. More sellers will also lead to better selection. All of these effects will come full circle back to a better customer experience.

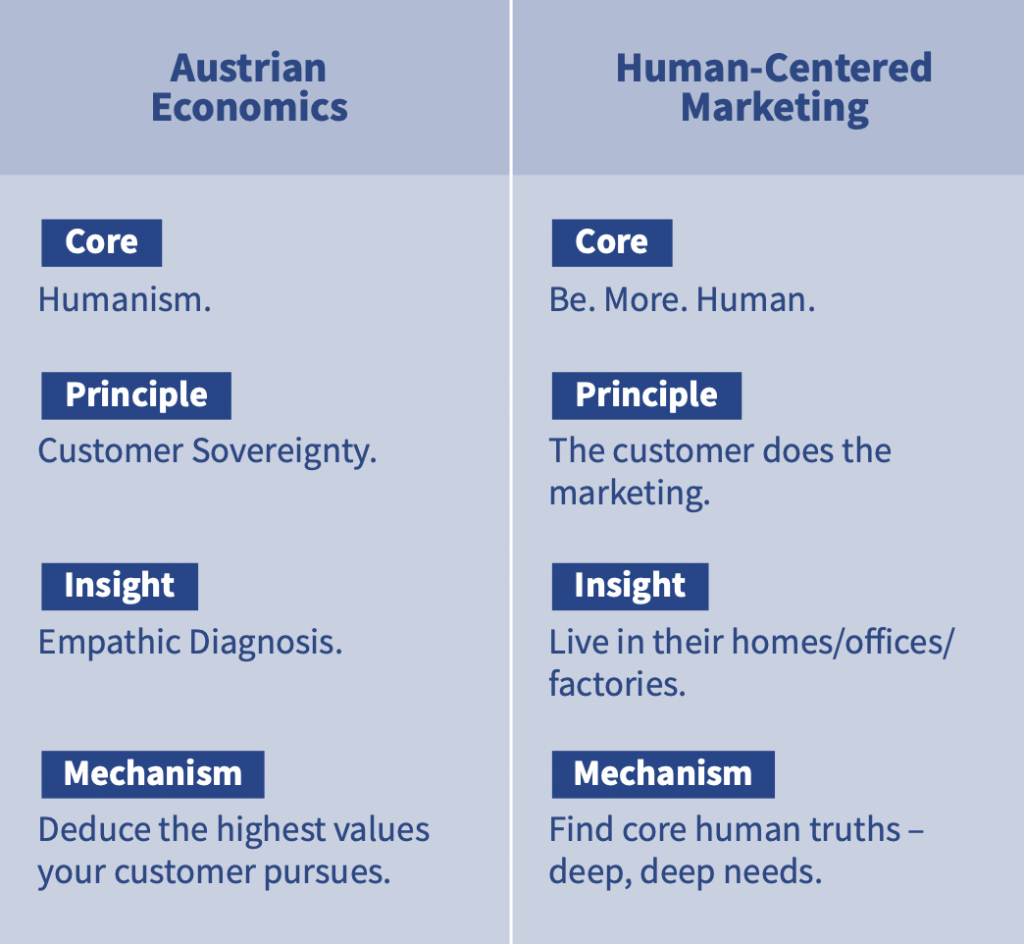

John Tamny sees the American entrepreneurial economy as a beautiful and productive flywheel.

Why are Americans so entrepreneurially focused? We descend from “the crazies” – the other thinkers who came from around the world, dissatisfied with their lives, and willing to cross oceans and borders to get to a place that offers no security but offers freedom. They took the ultimate entrepreneurial leap. We got the nut cases. Steve Jobs, for example, was of Syrian descent. Could he have started Apple in Syria? No.

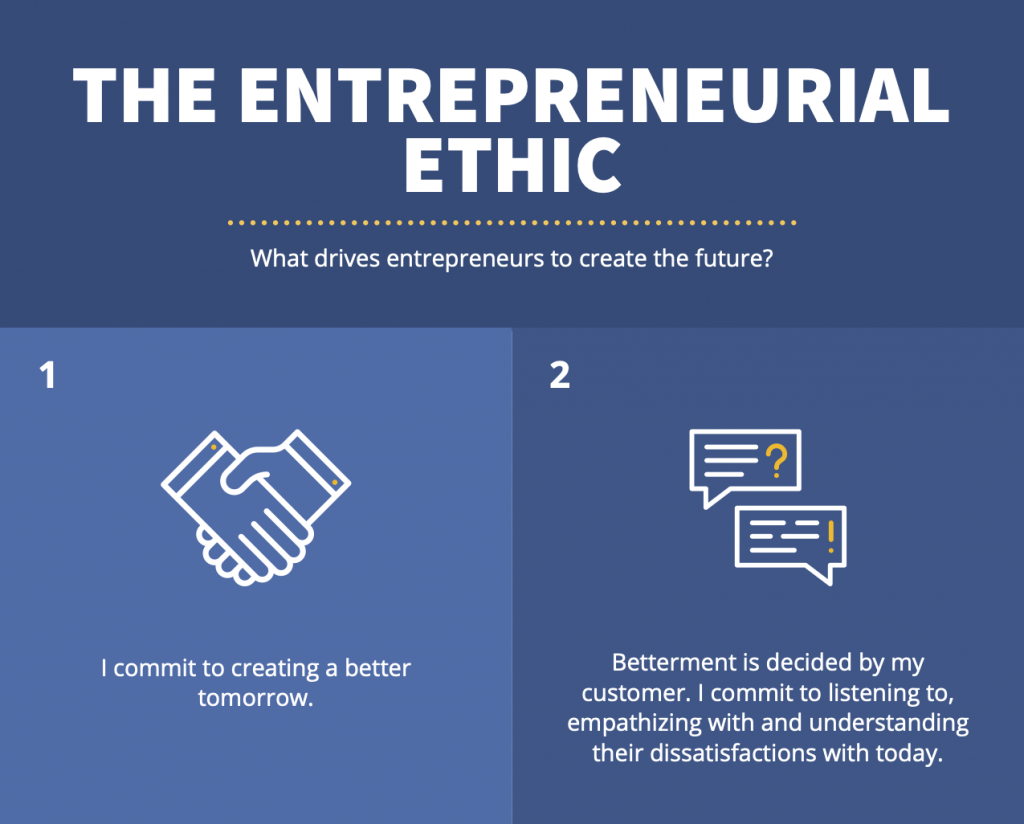

Entrepreneurs lead us to a better place.

John’s definition of an entrepreneur is someone who has a vision that everyone else thinks is ridiculous, yet they follow it anyway. They have no time for the way things are done today. They want something different. And to win consumer acceptance, what’s different must also be better. So they quite literally lead us to a better place. Horse-drawn carriages weren’t enough, so Henry Ford gave people something different. Everyone wanted Blackberry phones when Steve Jobs brought out the iPhone, and he quickly demonstrated its superiority. Every entrepreneurial act is speculation – there is never certainty that people are going to want the new product. That’s what is so important about entrepreneurs.

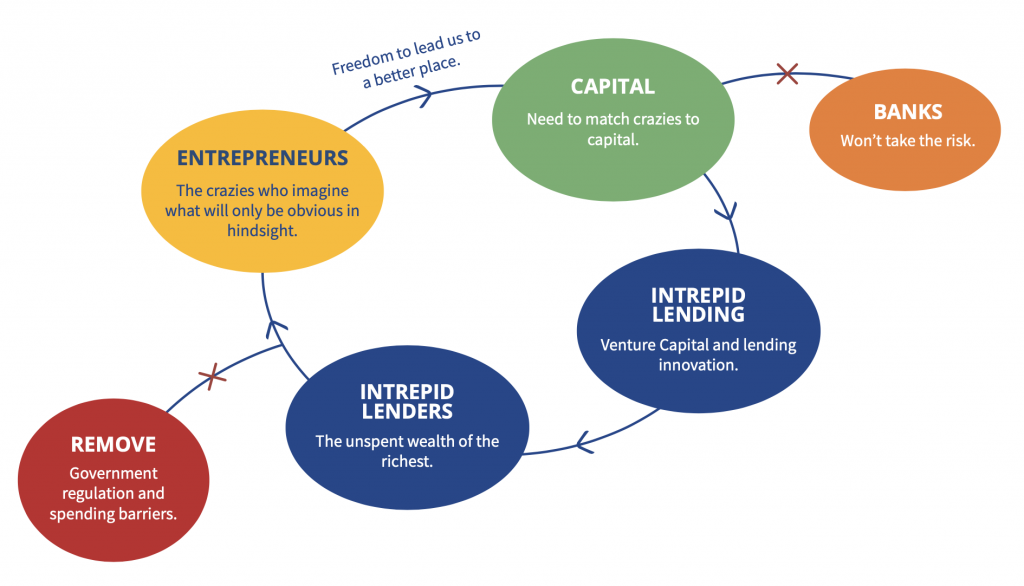

Entrepreneurs need to attract intrepid finance and intrepid financiers.

Silicon Valley is littered with VC’s who turned down Facebook, and turned down Amazon. Founding entrepreneurs think differently and have a vision that is far out of the norm, and they need to be matched with financiers who can be strong supporters and collaborators on the path to a better place. Irrespective of whether it is from Wall Street or Sand Hill Road, or from visionary friends and family, it’s critically important that we figure out a way to get financing to brilliant people. Government restrictions on entrepreneurial activity are certainly barriers to growth, but so is failure of imagination on the part of capitalists.

Intrepid lending takes place far away from banks. Unspent wealth is the source, and the more unspent wealth one person has, the more risks they can take.

We tend to complain about the antiquated and sclerotic banking system, but it has nothing to do with entrepreneurs and innovation. Banks make loans to entities they know will pay them back. Entrepreneurs fail 90% of the time. Banks want nothing to do with innovation.

Those with unspent wealth are the most crucial people in the economy when they match their unspent wealth with entrepreneurial talent and vision. The more unspent wealth they have – and the less the government takes away from them in taxes – the more intrepid they can be in investing it. When we tax away the wealth if the richest, we tax away the most important wealth of all. – that which has the highest odds of being directed towards new ideas that, while they look promising, have high odds of failure.

More and more of us have the opportunity to become entrepreneurs, if we harness the flywheel of original ideas that attract intrepid capital.

One of John’s many books, The End Of Work, describes how we are all now so enabled with interconnectivity to resources that we have the chance to make money by doing what we love. Our passion can become our job. If we are able to imagine a future place that is better – that improves the lives of individuals – we can create a growing business. The more of us who can do this, the more we grow the whole economy – which, after all, is made up of individuals. If we can also attract that intrepid capital that John refers to, growth becomes faster and higher.

Besides The End Of Work: Why Your Passion Can Become Your Job, John’s books include Popular Economics: What The Rolling Stones, Downton Abbey and LeBron James Can Teach You About Economics, and Who Needs The Fed: What Taylor Swift, Uber, and Robots Tell Us About Money, Credit, and Why We Should Abolish America’s Central Bank.

Free Downloads & Extras

“John Tamny’s Entrepreneurial Flywheel”: Our Free E4E Knowledge Graphic

Understanding The Mind of The Customer: Our Free E-Book

Start Your Own Entrepreneurial Journey

Ready to put Austrian Economics knowledge from the podcast to work for your business? Start your own entrepreneurial journey.