72. Peter Klein: Four Considerations for the Delegation of Derived Judgment

Business books and business school courses tend to think of organization design as the structuring of a hierarchy, or the linkages of nodes in a network. The boxes and lines are departments, executives, assignments and communications flows.

Professor Peter Klein invites us to think in a different fashion. Organization design is the distribution of judgment among collaborators. The judgment of many people is necessary to the firm’s existence and value-facilitating practices.

Key Takeaways and Actionable Insights

For entrepreneurs, the future is not risky, it’s uncertain.

Risk is a calculable mathematical probability, like the result of 1000 tosses of a (fair) coin, or the likelihood of you being involved in a car accident in 40 years of driving on US interstate highways.

The outcomes of entrepreneurial decision making are not calculable. They can’t be computed. Yet entrepreneurs need to make decisions, without having all the facts in hand today, and without knowing the odds of the future results. That’s uncertainty.

Therefore they exercise judgment. Judgment is action. It’s business practice.

Judgment is not guessing, or speculating, or hoping. Judgment is action. Specifically, judgment is taking ownership of property and resources, combining and recombining them in different ways, and using them to make a product or service to offer to the market.

Judgment also incorporates spirit: the imagination, energy, creativity and bravery that entrepreneurs apply when they act. Judgment is human action.

And judgment is continuous. Entrepreneurs are called upon every minute of every day to make decisions of judgment.

Judgment quickly becomes team action.

As firms grow, the founder can’t be the sole exerciser of judgment, or the only one making commitments or acting creatively and imaginatively. In larger, more complex, multi-divisional forms, there are many executives, managers and employees who will be called upon to make judgments. And they will be well-qualified to do so, since they have special skills and tacit knowledge that the rest of the firm, including the founder, do not have.

In fact the founders or owners (or Board Of Directors) actively seek the judgment of the whole firm, in order to achieve the highest level of business success. Often, they make sure that everyone in the firm has enough “skin in the game” (in the form of incentives, commissions and supplemental compensation) to motivate them to give their best judgment.

How does judgment apply in complex organizations?

The firm develops a mix of original judgment and derived judgment (see Mises.org/E4E_72_PDF).

Derived judgment is Peter Klein’s term for the delegating of decision-making power and its distribution throughout the firm. Original judgment — the ultimate decision-making power — rests with the entrepreneur-founder, or may reside with a Board Of Directors or an appointed CEO. Derived judgment is granted to others throughout the firm who have special knowledge and skills to act creatively and imaginatively on the specific uncertainty they face in their positions.

The skill of original judgment is selecting the right people to exercise derived judgment, and designing the right combination of motivating incentives and appropriate controls.

What’s the best combination of incentives and control?

Austrian subjectivism and individualism, along with opportunity cost analysis, can point the way to the best mix of incentives and control.

Subjectivism tells us that there is no objective right answer to questions about which decision rights the owner should delegate to which employees under specific circumstances. The answer to those questions depends on the particular circumstances of the venture, its technology, its market, its business environment, the characteristics of the employees and the characteristics of the owner.

Individualism tells us that there are no generalizations about people — each one has different knowledge and skills and characteristics like reliability or trustworthiness, as well as creativity and imagination. The entrepreneur must judge each one individually, and match them as well as possible to specific circumstances.

Opportunity cost analysis tells us to always weigh the potential upsides and potential downsides of each choice and each appointment of an individual to a position in which they can exercise derived judgment. Exercise judgment about judgment.

Consequently there are four considerations:

- Be as sure as you can to choose the individual with the most (and most relevant) tacit knowledge for the area in which they are going to exercise derived judgment.

- Choose the individual who adds the greatest amount of experience as possible to the relevant knowledge.

- Make sure the derived judgment of managers and employees is guided by a well-articulated mission (why we do what we do) and business model (how we do what we do). Pay attention to how well these are understood and shared.

- Balance knowledge and experience against the potential for abuse (misjudgment) and the potential cost of that abuse should it occur. Don’t risk “destructive entrepreneurship”.

There are no “bossless” organizations.

Peter Klein points out that even in the flattest of organizational designs (think Wikipedia, Zappos, Spotify, or W.L. Gore) there is always some kind of governance, either of rules or of hierarchical authority, to limit the risk from derived judgment gone awry.

Don’t design an organization with an excessive amount of derived judgment relative to the controls that are in place.

How good are you at original judgment and at delegating derived judgment?

Entrepreneurship in action is real people in real-life situations. It’s not theory. Some are going to be better than others, as indicated by results and outcomes.

It will be useful for you — although not definitive — to self-assess your entrepreneurial judgment and how you delegate it. Gallup’s Builder self-assessment promises to help you build a thriving company and a winning team. Personality assessments like the Big 5 are less specifically tailored to entrepreneurial judgment but can nonetheless shed some light on personality traits that are applicable in entrepreneurship, whether in a small business, a growth firm or a corporate structure.

Free Downloads & Extras From The Episode

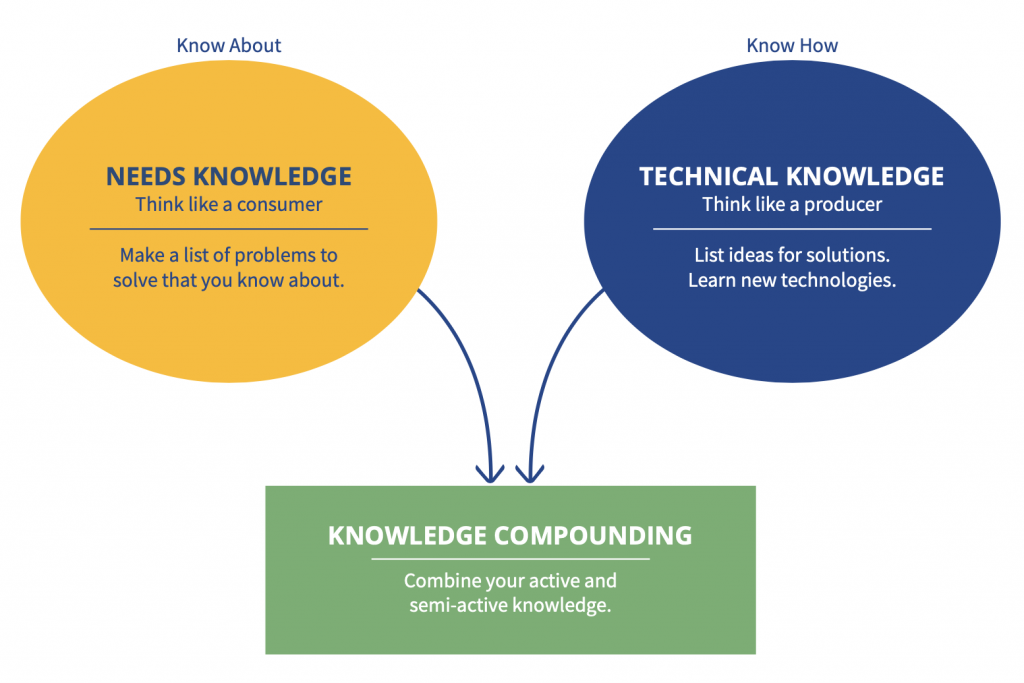

Uncertainty and Entrepreneurship: Our Free E4E Knowledge Graphic

Our latest free e-book, Austrian Economics in Contemporary Business Applications: (PDF): Our Free E-Book

Start Your Own Entrepreneurial Journey

Ready to put Austrian Economics knowledge from the podcast to work for your business? Start your own entrepreneurial journey.