Group Of Nations Embraces Inclusive Entrepreneurship To Reduce Global Poverty.

In The Ethics Of Capitalism, leading economist Jesus Huerta de Soto argues that the most just society will be the society that most forcefully promotes the entrepreneurial creativity of all the human beings who compose it. When we think of a global society, we can then understand that entrepreneurship is the path away from injustice, and from poverty, for all the world.

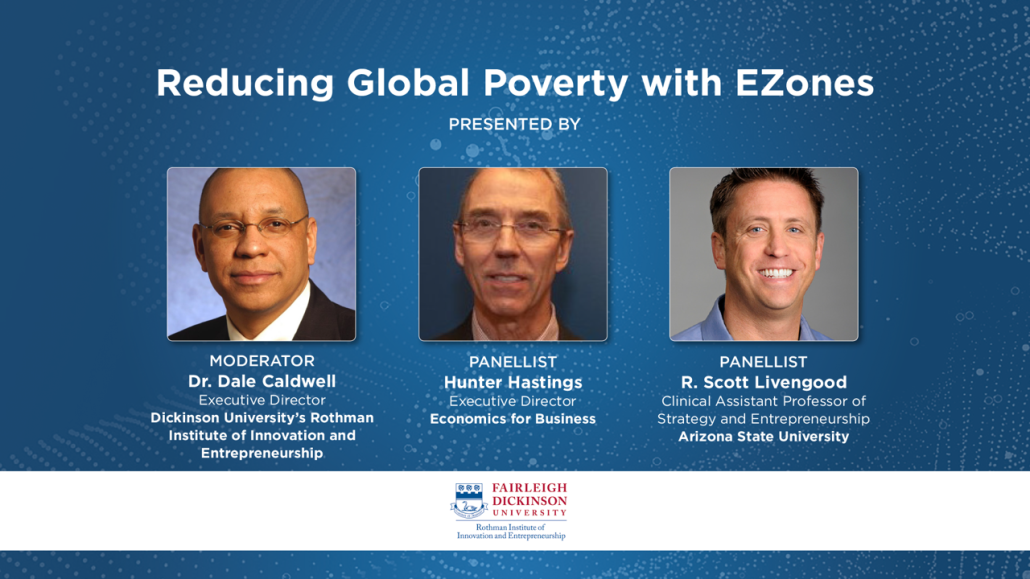

At the G7-G20 Solutions Through Inclusivity Virtual Summit on Nov 17, 2021, I’ll be making this case along with my colleagues Dr. Dale Caldwell from Fairleigh Dickinson University and Professor Scott Livengood from Arizona State University.

Entrepreneurship is a philosophy of universal individual creativity and capability. Everyone has a sense of how the world can be made better, and entrepreneurship is the universal method of achieving that betterment. It starts with an attitude that all people share: a continual eagerness to seek out, discover, create or identify new benefits, and better conditions. Economists use the term value – a feeling that the new circumstances suit people better than the status quo. People aim at experiencing value.

Entrepreneurial creativity is a shared activity of consumers and producers. It’s hard to say where it begins, and the co-creation never ends. We might say that consumers or customers initiate the process by expressing dissatisfaction – the feeling that things could be better, and they’re not better yet. They don’t know the solution to their dissatisfaction, and they may not be able to articulate it very well, but they have the feeling. Every human being feels it in some way, every day, everywhere in the world. Dissatisfaction is a universal resource for entrepreneurial initiative.

The role of the entrepreneurial producer is to sense this dissatisfaction. The entrepreneur’s antennae are always up and quivering, scanning the environment for dissatisfaction they can utilize as the source of an idea. There’s a skill for doing this well: we call it empathy. Empathy is the ability to think as if you were inside the customer’s mind, feeling what they are feeling, experiencing their emotions. Empathy can be refined as a business skill, but it’s inherent in everyone. It’s how the human race gets along. It’s the principle behind every trade and every exchange. The entrepreneur understands how to make the customer feel less dissatisfaction, and more satisfaction through trade. The closer the entrepreneur and customer are connected – the deeper the empathy – the better the producer becomes at satisfying the need, and the happier the customer becomes in the confidence that their needs can and will be met.

All of these feelings, this empathy, and this creativity come naturally to people all over the globe. Entrepreneurship is the human condition. It’s the social coordination function of matching people’s most important wants with the available resources and goods and services that fulfill those wants.

Where people might need some help is in implementation of this coordination function. That’s where the concept of Entrepreneur Zones or EZones comes in – the idea that Dr. Caldwell and Professor Livengood and I are presenting to the Group Of Nations. The word “Zones” implies a physical location – and that’s exactly what we envision. An EZone can be located anywhere in the world, and it’s particularly appropriate for the energetic uplifting of a place that is currently in need – a developing nation, for example, or an underdeveloped inner-city in any of the developed countries, or a community anywhere.

One of the steps in EZone development is training – encouraging the entrepreneurial mindset and communicating the steps of the entrepreneurial process. It’s a knowledge process and the requisite knowledge is available to all: it’s subjective (we all have individual knowledge); practical (how to help people); it’s exclusive because it’s individual and that has immense economic value; tacit, meaning it’s not well articulated, but we can draw it out of people through encouragement; and it’s creative, i.e. doesn’t require any resources, it’s developed out of nothing. When people understand the economic worth of their own knowledge, then we can teach them how to apply that knowledge in helping others to improve their lives. There are many pathways available to them. The formal technique is the value proposition, which includes a precise identification of the customer and their wants, and a precise description of what offer the entrepreneur will develop to assuage their wants. This proposition is easily testable – we can teach that, too.

A tested value proposition requires a business model and a development process to bring it to market. The process is also teachable and demonstrable. Part of the process is assembly of resources, including capital, but also supportive services and supply chains. We can teach the assembly methods, and make connections to all the resources, including how to negotiate, contract and collaborate in win-win arrangements.

Professor Livengood teaches entrepreneurship at the university level in the USA, and he has also gained first-hand experience with transferring and recalibrating that training for the poorest displaced refugees in camps in Africa. He discovered that the principles, processes, and practices remain the same, and that language and communication must be fine-tuned to the specific audience, in order to give them the confidence that successful entrepreneurship is in their reach. Dr. Caldwell is an active pastor as well as a university professor, and he has intimate first-hand knowledge of the entrepreneurial potential of people in deprived communities. Both Professor Livengood and Dr. Caldwell exemplify the multi-level applicability of the entrepreneurial method to the pursuit and achievement of prosperity for everyone.

Entrepreneurship is the best path upwards for every community. It’s moral, ethical, and economically sound. Entrepreneurship is the engine of prosperity and growth. It’s exciting and energizing for everyone in the community. The economic gains are broad and deep. Families are strengthened through both shared purpose and reliable income. The kids are better nourished and perform better at school. Violence and anti-social behavior are reduced because people are concentrating on economic opportunity. Jobs are created so that everyone in the community feels their own part of the opportunity. New services are drawn to the EZone, improving the quality of life. Larger companies come to town, attracted by the high-energy workforce and the quality of life in the community. The entrepreneurial community connects to the world and serves markets all over the globe while receiving new inbound services. Improved technology comes to town. Churches enjoy more attendance and their pastors feel renewed. The uplift is general and universal. There’ll be more communities looking over, liking what they see, and jumping on the bandwagon.

You can see the agenda for the Group Of Nations Summit here, register to attend here, and read more about the Solutions Through Inclusivity Summit here.