177. Mark McGrath On After-Action Reviews

The business-as-a-flow orientation embraces continuous adaptive change within the firm. Traditional slow-motion control mechanisms like strategy and planning are no longer appropriate. The new toolkit that entrepreneurs are developing includes the after action review (AAR), a learning tool rather than a misguided attempt at predictive control.

Key Takeaways And Actionable Insights.

In a VUCA world, entrepreneurial orientation embraces change and adaptation in order to reach goals.

Learning fast is critical in times of accelerated change. A business firm must change at least as fast as its market and its external environment if it is to survive and thrive – ideally faster. In earlier podcasts, we’ve made reference to the OODA loop as a non-linear change management framework: Observe changing data, filter those Observations through your firm’s capabilities, culture, heritage, and experience to understand what the new data means to your firm specifically, re-Orient if it’s indicated, make new Decisions and take new Actions, and monitor the feedback loops for updated Observations. Speed of progression through the loop is a competitive advantage – make changes faster than your competitors.

One of the keys to successfully managing change is a bias for action.

It’s possible that in some situations some businesses may fear taking action – they lack confidence in their own hypotheses and are concerned that their action might be “wrong”. Austrian entrepreneurship takes a different perspective. Entrepreneurial orientation and intent shape decision-making by giving it a high potential focus and, thereafter, every action is framed an experiment from which to learn. Learning enables a greater capacity for reframing. Curt Carlson, in E4B podcast #175, told us that relentless reframing is key to success in innovation. Learning through action is paramount.

The tool for learning from action is the AAR – After Action Review.

The After Action Review is a simple device that asks the questions: what did we intend would happen, what did actually happen, what can we learn from what happened, what will we change next time we take action.

- Intent – What are the intended results and metrics?

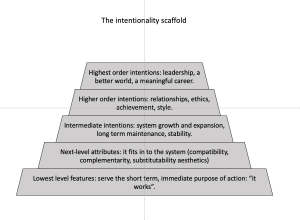

It’s important to continually review the shared understanding of intent among those participating in any action or project or initiative. Shared intent is the mechanism that supplies direction and thrust so that everyone is moving in the same direction. It’s sometimes called commander’s intent (in the military) or leader’s intent (in Agile team science). It’s key that every team member subscribes to and can articulate the intent.

- Performance – What happened? Is there a performance gap compared to intent?

“What happened” can be a challenging question because observation is often subjective, and individuals in different vantage point and with different perspectives can provide different reports or estimations of what happened. Cultural factors become important – front line actors and individuals located lower in a hierarchy must be able to speak freely about what they observed without fear of contradiction or condemnation by superior. A performance gap must be viewed as a learning opportunity that is good for the entire team and the firm as a whole.

- Learning – What was the cause or source of any performance gap?

In a high-speed learning culture, teams are eager to identify causes or issues that give rise to performance gaps. In complexity thinking, it is not always possible to identify linear cause-and-effect linkages, but it’s generally possible to identify areas for improvement as a result of experiencing a setback. It may simply be necessary to run more experiments until a better performance can be attained. It may be possible to identify obstacles that can be removed. It may be possible to identify risks that can be mitigated. In any of these cases, learning via experience (i.e., after action) advances knowledge and augments adaptiveness.

One possible learning is that the intended result is not, in fact, within the capacity of the firm, leading to either a decision to augment capacity or a decision to redirect existing resources into other lines.

- Next Time – What should we change?

Learning leads to new hypotheses which can be implemented through new action. The After Action Review identifies what changes in behavior are appropriate to try in a future action. There’s the opportunity to eliminate waste, or abandon no-longer promising trials, or experiment with improved ideas. In a learning culture, there is eagerness to return to action armed with new knowledge and to explore new potential.

AAR’s can span all time periods: before action, during action, after action.

When should a firm conduct AAR’s? All the time. In fact, there’s a role for before action reviews, during action reviews and after action reviews. All have the same structure.

- What is / was / is going to be our intent?

- What challenges will we expect to face / are we facing / did we face?

- What have we learned in the past / what are we learning right now / what caused the latest gap?

- What will make us successful this time / what adjustments should we make right now / what will we change next time?

A learning culture and orientation are critical to the successful application of AAR’s.

Learning via AAR’s is not mechanical, it’s cultural. The culture of the firm must be that there’s no development, no progress, no improvement without learning. Mark McGrath links the learning culture to the growth mindset. The relevant assessment is not one of strengths versus weaknesses but the mindset of the firm compared to that of its competitors. Seeking growth is a mindset, and so is learning. It’s a humble mindset in which we recognize our bounded understanding and seek eagerly to augment it with new knowledge.

There are simple shared rules for individual AAR’s and for the learning culture: shared goals and mental models, open to every level of the organization, psychological safety, transparency, shared findings, preparation for next time. Within these rules, every firm can build a capacity for learning that becomes a capacity for growth.

Additional Resources

E4B AAR template

Background reading – nextforge.com

Orientation: Bridging The Gap In The Austrian Theory Of Entrepreneurship (AERC 2022 Paper)

Mark McGrath on LinkedIn