Why Study Economics?

Economics is the science of human thriving. It is the study of human choices and the motivations behind them. If we can understand those simple things, we can understand every transaction between humans as consumers and humans as producers, and roll that micro understanding up into the more macro understanding of firms and economies, and how they function, succeed and grow.

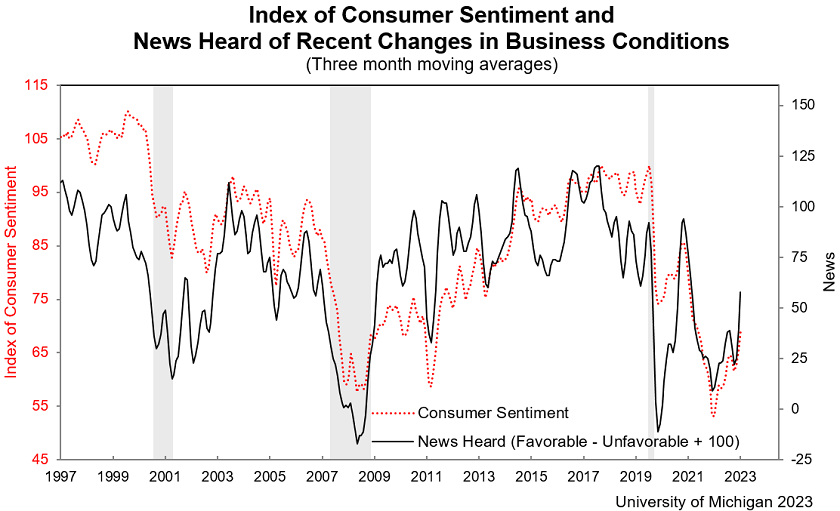

Thriving is what we all want. We can define it as continuously increasing our feelings of well-being. And that’s the first indicator of the value of economics. The output of any economy, of every firm and of every exchange and every transaction is more well-being – the feeling of being better off. Yes, a feeling. Economics is not measured in numbers like GDP or firms’ revenues or profits. It’s assessed by the satisfaction of individuals as to whether things are getting better or not. A growing economy is one with improving feelings of well-being. The nearest thing to a metric for this feeling of well-being is the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index.

When the index is high, it’s associated with increasing stock market valuations, economic growth and prosperity. When it’s low, it’s associated with recessions. There’s no need to search for cause-and-effect, because it’s not there. The sentiment is emergent from the system.

A successful firm is one whose customers feel increasing well-being – more satisfaction, more confidence, more trust, more relatability. A strong balance sheet is one with assets that will facilitate such satisfactions and feelings of well-being many years into the future. A strong P&L is one that shows that customers are generating the cash flows that result from their willingness to pay for those satisfactions at the price the business chooses to set and results in profit.

How does economics teach us to increase well-being? Development economics as its called – the study and theory of how economic growth is generated – is a highly underdeveloped field. It has no answers because it’s looking for those cause-and-effect conclusions that just can’t be found. It’s better to look at system effects: what is the system most associated with increased well-being? It’s free market capitalism.

More entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurship is the function that drives growth in the free market system of capitalism that brings prosperity. Entrepreneurship is misunderstood by most economists and all policymakers. Entrepreneurship is the economic function that creates new value, and value is what we all seek. Value is the feeling of being better off after experiencing a good or service that’s been prepared for us or sold to us. It’s the feeling of betterment – better off today, and better off tomorrow because of all the great offerings entrepreneurship brings to us. Entrepreneurship is what drives capitalism. It can take place in a startup or in a giant corporation, so long as the intent is to improve customers’ lives. It is highly restricted in an economy where government regulation strangles innovative opportunity, or where government directs investment funds to one industry rather than another – for the simple reason that entrepreneurship is experimentation to find out what customers prefer, and regulation often doesn’t permit experimentation. What drives growth? Those of us who are not entrepreneurs don’t know – we leave it to entrepreneurship to run the crazy experiments that will help the rest of us to find out.

Production before consumption.

The conventional wisdom of economic pundits and government planners is the opposite of the entrepreneurial view. They believe that consumption – what they sometimes call aggregate demand – is the driving force of the economy. If the economy, as they measure it, slows down or stalls, their answer is to put more spending power in the hands of consumers so that they buy more products and services. They believe that demand brings production into being. Without demand, there’d be no production. The opposite is the true case. Entrepreneurs reveal to consumers that there is more they can want – better goods and services, new technologically innovative products, faster deliveries and lower prices. By demonstrating the availability of more – by producing, that is – entrepreneurial businesses generate demand for their offerings. Demand does not bring businesses into existence; businesses bring demand into existence. Any and all restrictions on production should be lifted to bring productive growth to any economy anywhere in the world.

Less quantitative, more qualitative.

Economics is usually presented as a quantitative science. Economic “quants” focus us on numbers like GDP or economic growth rates or trade imbalances or debt levels. They want us to think of economics as a science on par with physics and mathematics. But it’s not. Economics is about well-being, and how humans increase well-being for themselves, their families, their firms and their communities. Well-being is subjective, a feeling on the part of individuals. It can’t be measured, enumerated, ranked or stacked or trended. Economics aims for a world in which we can consciously and deliberately raise and expand and extend well-being, without always trying to capture the improvement in numbers. Feeling better off is a qualitative phenomenon.

Less economic policy.

The word policy should never be conjoined with the word economics. Policy equates to politics, i.e. a biased, group-interest driven perspective on economic decision-making. Economics teaches us that markets can freely determine all allocation decisions, and all selections between what individuals and groups prefer, favoring new and better and jettisoning what’s out-of-date and inferior. Politicians may not always like market choices, and may therefore introduce policy that contradicts the markets, but this always leads to less total well-being. And since there is no possibility of isolating cause and effect in a complex economic system subject to an incalculable number of influences, interactions, constraints, and unanticipated feedback loops, policy never “works” – it can not lead to the outcomes it promises.

Students of economics will understand and appreciate these catalysts for well-being – that’s why economics is worth studying.