Jeff Deist, President of the Mises Institute, recently penned a metaphorical comparison of Austrian economics to the punk rock bands of the 70’s and 80’s who composed, created, and played but were denied recognition because they were locked out by the music industry establishment. They developed a do-it-yourself ethic when it came to publishing and touring and promotion; they referred to their own music as unheard. Jeff’s metaphor is that Austrian economics is unheard today, locked out by the neo-classical mainstream and its academic and publishing establishment.

Jeff pointed to specific areas of economic theory where Austrians are unheard, but have the chance to be vindicated when outcomes confirm Austrian insights: money and monetary policy, malinvestment resulting from bad monetary policy, misallocation of resources as a result of socialist welfare policies, the bureaucratic mismanagement of the interventionist state, and economic distortions that favor a political elite.

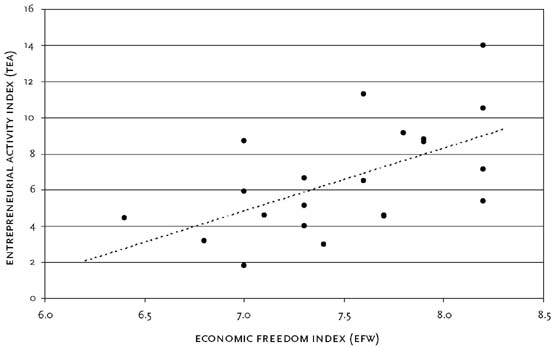

This is all macroeconomics. There is a field where Austrians are being heard and where Austrian theory is tremendously influential, and that field is dynamic entrepreneurial capitalism. To be sure, this is not a locus of government policy. Neither government nor mainstream economics recognizes the role of the entrepreneur in the economy. The Austrian school, on the contrary, defines that role, and builds a cogent theory of innovation, economic growth and individual and social betterment on entrepreneurship. Austrian economists build a necessary bridge between economic theory and strategic and organizational management studies.

There are elements of Austrian economics that are uniquely suitable for building this bridge, including:

Individualism

The unit of analysis for the Austrian school is the individual, both as producer and as consumer. The consumer is sovereign, the captain of the economic ship. The entrepreneur is the helmsman, steering toward the goal that the sovereign consumer sets. Each role is aimed at improving the individual’s circumstances. The two roles interact with the result of betterment for all. Mainstream economics start from a different place, with the focus of analysis on false aggregates, like GDP, money supply, the price level and even “gross” supply and demand. Austrian economics can help individuals make better decisions, both as producers and consumers, and that recognition is beginning to dawn.

Subjective Value

Austrian value theory is unsurpassed in its ability to help producers with the critical economic task of value creation. Value is a consumer perception, and occurs exclusively in the consumer’s mind. Therefore, it is the consumer who creates value. The descriptive adjective “subjective” means that value is personal, emotional, idiosyncratic, and inconsistent. It most certainly can not be modeled or “formalized” in any way, which places it well outside the boundaries of modern economics. Yet value creation is central to civilizational progress, economic growth, and the success of firms. Austrian economics holds the exclusive key to the understanding that guides these processes, a key that is highly prized in the business community, if not by government and its economists.

Entrepreneurship

In Austrian economics, the role of the entrepreneur is to sense, through the application of empathy, the dissatisfactions of consumers — the signal that they are not experiencing the value they seek — and to rearrange resources into a solution that addresses that dissatisfaction. Because value is subjective in the consumer’s mind, and because the future is unpredictable, entrepreneurs exercise what Austrians call judgement: the commitment to action required to bring their new solution to market for the consumer despite the uncertainty of a profitable outcome. Mainstream economics is unable to comprehend entrepreneurial judgment. Why do 9 out of 10 entrepreneurial initiatives fail? Because, explain Austrians, such a high failure rate is to be expected as a consequence of high levels of uncertainty, consumer subjectivity, the limits on present knowledge. These cause entrepreneurial initiatives to be experiments in new knowledge creation, and the rivalrous actions of multiple entrepreneurs conducting contemporaneous experiments so that the sovereign consumer can choose the best one. Entrepreneurship is the dynamism of the unhampered economy, as more and more people are beginning to understand.

Austrian Capital Theory

In the real world, as opposed to the world of economic models, Austrian capital theory (ACT) provides a guiding light to entrepreneurs on how to assemble, organize, and manage their companies. In Austrian economics, capital is called heterogeneous. That means, every unit of capital is different, and entrepreneurs can combine these units in innumerable ways, reflecting their own knowledge, preferences and experience, and the results of their previous experiments. They can continue to reshuffle and recombine assets in dynamic adaptation to market signals, so that the resultant capital structure can be viewed as unique. The value of the capital structure is based on its ability to facilitate the experience of value by the consumer, so that the entrepreneur-assembled capital structure reflects consumer preferences. This is all anathema to neo-classical economics and its static concept of the production function. For entrepreneurs, ACT guides them toward dynamic and flexible capital structures and new forms of organization which facilitate that dynamism. Modern “virtual” organizations and new commercial processes such as Direct-To-Consumer are reflections of the insights of ACT.

Innovation

Modern mainstream economics lacks a theory of innovation, primarily because there is no role for the entrepreneur. The field has been left to business writers who attribute it to creativity in the “design process,” and promote innovation processes and innovation workshops. In Austrian economics, innovation emerges as the result of consumer sovereignty, subjective value, and entrepreneurship. Austrian economists can help businesses to innovate not through process and tactics, but through understanding the mind of the sovereign consumer (via insights tools such as the means-end chain), capacity development, and dynamic resource allocation accelerated by consumer-response capabilities.

In addition to these principles, entrepreneurship is also a decentralizing process. Knowledge is highly distributed, and because entrepreneurial initiatives stem from individual entrepreneurs’ empathic knowledge of a small number of consumers’ dissatisfactions, so is entrepreneurial action. Entrepreneurial specialization will tend toward increasing narrowness in the search for unique capabilities and unique capital combinations. This decentralization runs counter to the centralizing tendency of government regulation and intervention and of crony capitalist and globalist corporations. In this sense, the dynamic entrepreneurial capitalism of Austrian economics represents not only a route to personal and societal betterment, but also a better route to freedom than political action.

See, for example, The Theory Of Dynamic Efficiency, Jesus Huerta de Soto, https://www.jesushuertadesoto.com/the-theory-of-dynamic-efficiency/

Bureaucracy, Ludwig von Mises, p226 https://mises.org/library/bureaucracy