Customer Value Is All That Matters In Business.

Value creation is – or should be – the number one concern of every business and everyone in business. The term means value for customers. If a firm does not generate value for customers, it is not in business and can’t possibly serve other constituencies like employees, shareholders, stakeholders, and local communities.

Businesspeople must think deeply about value and understand it fully, and it’s not always the case that they do. Let’s start at a higher level than the business firm, at the level of the economy. What is an economy? It’s how well-off a group of people make themselves with the resources they have available to them to work with. It’s the shared well-being of that group of people. It’s their quality of life, their enjoyment, and their satisfaction. In other words, the economy is not just the goods and services we produce or the dollars we exchange with each other to buy and sell goods and services. The economy is value that is generated for people – feelings of satisfaction, of joy and reassurance, and security, of meeting not just functional but also emotional and spiritual needs. The pursuit of economic value takes on purpose and meaning when it’s viewed through the eyes of people – and people are customers for business.

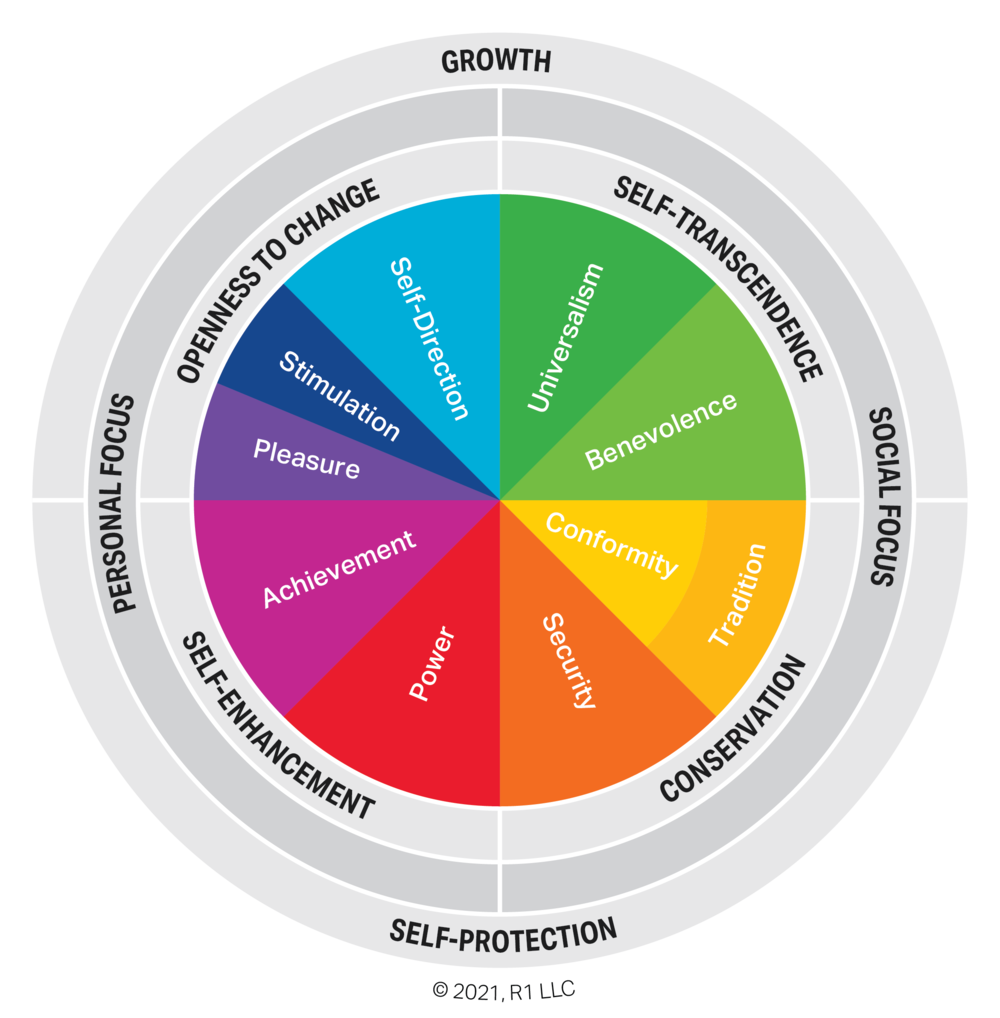

If we now return our focus to the level of the individual firm and its customers, we realize that value generation at this level in the economy must embrace and address the same feelings of satisfaction, joy, emotion, and spirituality. These feelings must be present in the value propositions that businesses make to customers. Each individual customer’s current state is a dynamic function of multiple values that they are trying to balance. You can refer to various analytical models for people’s value bundles. Here’s one called the Schwartz Theory of Individual Values. A quick look tells you that people are integrating values as diverse as pleasure, conformity, and security (and many more) into their everyday decisions and choices. The balance changes in every situation and from moment to moment.

Any business engaged with any customer at all must be conscious of the range of individual and cultural values that are in people’s minds and consciousness. If your customer is part of a firm in a B2B relationship with you, then you need to take account of the shared values of the firm you are dealing with, which will color and shape the decision-making of the individual you are engaged with.

From this perspective, value creation can be seen as pretty complex. Quite forbidding, even. How do businesses manage? There are a couple of simplifying approaches.

Get the direction right.

Value is a process. Your customer is continuously learning about value – what they themselves value in any specific situation and at any specific time. Their evaluation is changing. But they are seeking one direction, which we can call betterment: improving their feelings of satisfaction. Value is a change in status from one of less well-being to one of greater well-being. It is an increase in well-being. That means that you may not need to understand every nuance of the balance of the customer’s multi-functional values system. You just need to measure and monitor whether their feeling of well-being and satisfaction is moving in the right direction, towards betterment.

Get aligned.

While it is probably too demanding to try to identify every position of every customer on every vector of the Schwartz Value System or one like it, there is a less demanding way of value mirroring, and that’s alignment. If your position on your own value system is reasonably well aligned with your customer’s (you’re not in conflict, at least), and perhaps even better aligned than your competitor’s, then there’s a good chance of forming a value partnership: you make a value proposition that they can feel good about accepting. Alignment comes from an analysis of what matters. What matters most to your customer? You can ask them; it’s often very hard for them to articulate their values, but they might be able to answer a question about what’s important to them, at least at this time, in this situation, and regarding this deal. (Bill Sanders told us how just asking the question can “expand the value pie” in any contract negotiation with any customer.)

If what you think matters is close to what the client thinks matters, then there is the opportunity to become value partners, to make a deal or make a sale or make an exchange.

Empathy And Knowing Your Customer.

The business skill that underpins the generation of customer value is empathy. This is not a casual “get inside the customer’s head” routine. Value empathy is a product of the rapidly advancing knowledge of neuroscience that is spreading into business methods, combined with an understanding of complex adaptive systems thinking. Empathy starts from the concept of a mental model – a way of seeing the world and processing the information gleaned from sensory inputs – hearing, seeing, touching – into an individually cogent perspective. Every individual operates a unique and different mental model. The process of empathy is first to construct someone else’s mental model – the customer’s – and then run new information through it – the new value proposition that the business wants them to consider. If the business has constructed the customer’s mental model accurately, it should be possible to make a reasonable prediction as to how they will react to the value proposition. It’s not infallible, but it’s also not guessing, not projecting, and not wishful thinking. It’s not even marketing – that comes later if the business wants to attempt to change or modify the customer’s mental model. There’s a learning process, and humility is called for in thinking about customers’ complex mental processes.

Empathy is knowledge-based, unlike sympathy, which is emotional. Therefore, the more a business knows its customers and the more they know about their customers, the greater the potential for an accurate empathic diagnosis of the customer’s mental model. The first step in value creation is selecting the right customers for your business – customers you can know well and will enjoy knowing.

A Value-Dominant Business Culture.

Many of the criticisms aimed at big corporations today are the result of businesses’ failure to understand value. The claim to maximize shareholder value, but this is a financial calculation, not the generation of valued experiences for customers which is the true purpose of business. They claim to pursue stakeholder value, where the term stakeholder is amorphous, but generally taken to include employees, the population of the communities in which offices and factories are located, sometimes the environment, and sometimes even the government. None of these business activities fall under the true heading of value creation – only customer value fits. All else follows: profits (signals from the customer that they fully approve of the value they receive), stock price appreciation (reflecting the discounted future cash flows from satisfied customers), and stakeholder benefits (profitable companies with a loyal customer base are more likely to support all of their other constituencies).

Customer value takes care of all the other values. That’s why it’s all that matters.