A Radical New Vision Of Value Creation And The Value Roles Of Consumers And Entrepreneurs From Professors Bylund and Packard.

Hunter Hastings:

Mark and Per, welcome to this somewhat experimental edition of the Economics For Business podcast. Experimental in the sense that we’re going to have a three party discussion for the first time.

Mark Packard:

Hey Hunter. Hey Per.

Per Bylund:

Hey, thanks for having me, Hunter. Good to see you again, Mark.

Hunter Hastings:

With the occasion of having you both here at the same time is the recent publication of a coauthored paper, it’s called Subjective Value and Entrepreneurship. And it really advances and changes the thinking and logic regarding the implications of subjectivism for businesses, for entrepreneurs, it changes how we define value creation. It changes how business schools are going to have to teach value creation, it changes how firms are going to think about their business models, it changes how product engineers are going to think about product design. It really is a big breakthrough, I think.

Hunter Hastings:

So let’s start with I don’t know whether to say subjectivism or subjectivity, you’ll tell me Per, but it’s based on a area that we’ve covered before about value centricity. It’s subjectively experienced by the consumer, and therefore any entrepreneurial business action, whatever it might be, must be viewed through a lens of consumer subjectivity. So wouldn’t you start us off Per with the overview of what you and Mark mean, when you talk about subjectivity in entrepreneurship.

Per Bylund:

Sure, it’s not actually very strange for listeners to the Economics For Business podcast, because we’re saying pretty much what we’ve been saying here on the podcast for a while, namely, that subjective value is the direct experience, sort of good feel that you get, the emotions, everything that you directly experience as a consumer in your consumptive action.

Per Bylund:

Whereas what we’re doing in the paper is really reacting to how… There have been steps taken in the direction of subjective value, but they’re not exactly recognizing value as subjective, what they’re doing is rather seeing that… They’re assuming that value exists out there, in some form or another. And that we have different views of it, that we see it differently. And some of us can see some of them perhaps, but none other values.

Per Bylund:

Whereas what we’re doing in this paper is taking the full step and saying that no, value is your personal experience. It doesn’t exist in any other way. So it is, whatever it is for you personally.

Hunter Hastings:

So one way of just explaining the terminology, as we say, value exists in some way that would be objectifying it and you’re saying, we can’t do that. It’s entirely subjective.

Per Bylund:

Exactly. Yeah. It is your emotion, it is your feeling, it is your experience. And that’s end of story. That’s it.

Hunter Hastings:

Good. And so if we look through that lens to identify some of the applicability to businesses and firms, then let me start at the, what I call the point of the spear Mark, you say value is created by consumers, and not by businesses or entrepreneurs. And that’s the big non breaking statement at the outset. Business schools claim to teach value creation, but it bears no resemblance to that.

Mark Packard:

Yeah, it’s certainly not what’s normally taught in business schools. But to be clear, Per and I, and I think others of the Austrian School, we typically shy away from the language of value creation, we define value essentially, as benefit, an increase in individual well being.

Mark Packard:

So in this sense, value isn’t really created, it’s experienced by consumers, there’s no value if a consumer doesn’t experience it. If you have a product on your shelves, that is collecting dust, that product is not valuable, because no one has experienced value from it. And also, as Per was just saying, value is highly subjective. And it’s not just idiosyncratic, which means that it’s unique to every individual. It’s not even objective in any sense, it’s experiential. And that means that it’s different for everybody. And it’s dependent on your conscious view of and understanding of that value.

Mark Packard:

So everyone’s experience is different. We experience things differently. We have different physical and psychological and emotional makeup that puts every experience in an individually unique context. So value is never the same across individuals. It’s always unique.

Mark Packard:

So yeah value emerges or is experienced by consumers on the demand side and not on the supply side, it doesn’t emerge on the supply side, nothing is truly valuable ex ante. A resource doesn’t have value. A resource may be valuable to us or we might value a resource because we predict that it will contribute beneficially to one of these consumer experiences. But at that point, it’s only a prediction.

Hunter Hastings:

So pushing that a little bit further with value as an experience on the consumer side, you’ve talked about this before, but you repress it in the paper a little bit. It’s not even a one time experience, we can’t even narrow it down to that. It’s a process and more specifically a learning process. So take us through that, again, as you do in the paper, Mark, the implications of value as a process?

Mark Packard:

Yeah, I think this is a fascinating point, our lives and our whole human experience is this never ending value learning journey. Everything we do is toward a higher valued state, whether it’s production so that we can consume, or if it’s consumption, so that we can realize those benefits that we’re trying to get. But we don’t innately know precisely what we need, or even should want to make us as well off as possible.

Mark Packard:

From the moment that we’re born, we start searching for solutions to our pains, and our dissatisfactions. And we keep learning what to want and what not to want through our firsthand and secondhand experiences. And we keep changing and the world keeps changing. And there are new solutions to new problems. And until we reach what I call the Nirvana equilibrium, which we never will, where we’re perfectly and perpetually in a state of perfect euphoria, then we’re going to keep searching and keep learning and trying to resolve those remaining dissatisfactions.

Hunter Hastings:

And one of the ways you express in the paper Per that learning process, the consumer goes through is that they suffer from or they experience value uncertainty. So we often talk about uncertainty, and we tend to think about it on the entrepreneur side. And we’ll get to that in a second. But the consumers got uncertainty, too, they can’t know, at the point of purchase, or even at consumption, whether they’re going to experience value. So take us through the implications of that for the consumer.

Per Bylund:

And I think we all have the experience of buying a product and then being disappointed with how valuable it actually is, or how useful it is. And maybe we bought something and it sort of bought the idea of us being different people or it propelling us into a different career trajectory, or whatever or maybe it’s just a simple meal at a restaurant where we think that, “That sounds really great. And I’m going to try that.” And it’s not really all that satisfying.

Per Bylund:

So even when we have the product in front of us, and we can sort of extrapolate and guess what that good might do for us, we have an understanding or an idea of, and can imagine what it will get us and the experience we will get from it. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that, that is the experience we actually get from using the product. And that’s the uncertainty. So the more you have tried, the more experience you have, then probably you’re better at guessing how good that product is for you.

Per Bylund:

So what Mark mentioned in the learning process, that when you start out as a toddler, you don’t know a whole lot about anything. So you’re trying everything pretty much. But as a grown up, you know to stay clear of certain things that you don’t like very much, and so forth. But the problem is always a new product, a new good, a new thing to use that we don’t know exactly how this is going to satisfy us, even when we buy it.

Per Bylund:

And this of course translates to a huge problem for the entrepreneur because the entrepreneur needs to tell a story and sort of inform us of the possibilities and the value experience that we might get from the product, which is of course different for different people. But that’s why you have marketing and commercials telling a story and using pictures and colors and music and so forth to sort of convey to us as potential consumers that there is potential for value here.

Per Bylund:

Then the question of course is first do we believe it and then if we believe it, is it actually the case for us. So this, of course, goes back to the entrepreneur’s ability to sell us something more or sell us that service again. So when we go to a restaurant and we’re served a meal, and it was sort of poorly carried out, it wasn’t all that tasty that it looked like or whatever, we tend to not go back there.

Per Bylund:

So the entrepreneur’s problem is not only providing us with a good in the story, but also making sure that, in a sense, help us with a value uncertainty. And they can’t of course, because it’s our personal experience, but not lying is a good first step.

Hunter Hastings:

Yeah. And then just sticking with the consumer for a second. One of the props or tools that they use to do this evaluation work, you say is relativity, relativity of potential one satisfaction, I.E. they can at least go through the cognitive process of comparing the value proposition that’s in front of them with alternatives, and perhaps previous experience, you call it relativity marketing. That was your word. Can you explain that for us?

Mark Packard:

Yeah, that’s right. So everything that we value, we value relative to our opportunity costs, and actually more specifically to the alternative solutions that we typically use to satisfy that same need or needs as we understand them. So in other words to use Per’s example of the restaurant if I’m thinking about going out to eat for dinner, the value of a sushi place is not just relative to my valuation of other sushi joints.

Mark Packard:

It’s also relative to burger joints, and pizza joints, and steak houses and Indian food and seafood and everything else. It’s relative to all the other options that I have to satisfy that need. And you still have to go further than just these other restaurants, it’s also relative to the option of staying home and doing it myself, cooking my own meal. All of these options are available to me for the satisfaction of that hunger need.

Mark Packard:

And so I have to pick which is the best use of my time and money, for example, cooking at home saves me money, which I can use for other satisfactions, so to go out to eat, I have to give up those other satisfactions. But cooking at home also means I’ve got to clean up and do the dishes, which I also hate. So it adds an additional satisfaction component to that satisfaction experience, satisfying the hunger.

Mark Packard:

And so when you think about it, our minds do a remarkable amount of calculation when we choose and make these decisions. And most of it we do by instinct, which is pretty remarkable.

Hunter Hastings:

Yeah, I’ve got a picture of that going on inside my head every time I make one of those decisions, as you say, it’s pretty remarkable. Just as a sidebar, you did differentiate a little bit in the paper between consumers wants, and consumers needs. And I do personally get a little bit confused with that Per. So can you explain the distinction as you’re presenting it in the paper and how it might affect entrepreneurs thinking?

Per Bylund:

Sure. And Mark was sort of getting at that a little bit in his answer just a minute ago now. In the paper, we distinguished between a want, whatever is something you want, in a sense, it’s something you intend to use for satisfying whatever lack that you have, where I say need would be the core, sort of almost an objective component to it.

Per Bylund:

So Mark just mentioned the need to satisfy my hunger, which is not necessarily a want for any type of food. And it’s not necessarily a want for a restaurant either. So it’s broader. And this is sort of a little bit of a quibble, we have I think, about the relevance of distinguishing between wants and needs. Where I as an economist think that in a sense needs, it don’t matter, because we’re still acting on our wants, which is sort of an interpretation of how we can eventually get to those needs.

Per Bylund:

Whereas Mark would be more interested in the psychology aspect of it. And I guess we can discuss how relevant it is for entrepreneurs as consumers are still acting to satisfy their wants. But it could help to understand that there is a sort of a physical need behind a lot of products and a core that might be sort of objective that might be the same for a lot of people. I don’t know if Mark want to chip in here and give his sort of psycho analysis version?

Mark Packard:

Well, I will say that I’m right and Per’s wrong.

Per Bylund:

You got that wrong.

Mark Packard:

The way I see it and this goes back to kind of that learning model is that the need is, is critical, just because it is the satisfaction of the need per se that creates the objective experience from which the satisfaction and the experience arises. And so that… It is important to distinguish the wants from the needs, but the wants drive action, but the needs drive the kind of the response, the experience that we learn from and so influence future action. So that’s why I think it’s important.

Hunter Hastings:

So it has to do with consumer uncertainty in a sense. So you’re acting to satisfy a want, but whether that want actually satisfies a need? Well, that’s something you will find out for yourself in the experience. And the sort of discrepancy between the two is a big part of the uncertainty, right?

Per Bylund:

So I think that’s helpful. And I think of it in language, It’s much better if I’m a entrepreneur thinking about solving consumers wants or addressing consumers wants that’s the business I’m in and needs is some kind of higher state that the entrepreneur shouldn’t be thinking about. We use language about needs in a loose fashion that we should say once I think that’s how I interpret it anyway.

Hunter Hastings:

I want to take all of this, stay on the consumer side for a second. And I think what you’re telling is the consumer has work to do. They have this role of evaluating, and they’ve got some tools about relativity and the conditional nature of their decisions. But that’s a value processing task that they have. Is that a good way to think about the consumer’s role here?

Mark Packard:

Is this for me?

Hunter Hastings:

Either one, go ahead, Mark.

Mark Packard:

Yes. Our wants is perilous just explaining or actually predictive evaluations or evaluations, as I call them. That the predictions of value. And so we can imaginatively assess how much value we get from some new value proposition. And we formed once in comparing those imaginations but our value predictions are really fallible and uncertain, again, as Per was saying.

Mark Packard:

So when we consume, we also do what I call an assessment valuation. We reassess, or we assess that value experience itself, relative to our expectations of it. In fact, marketing theory argues that our experiences of satisfaction or dissatisfaction are actually comparisons to our expectations, they’re relative to those expectations. If we expected so much value, we’d be dissatisfied if we got less than that, even if it was actually pretty valuable to us.

Mark Packard:

So our expectations matter quite a bit in our value experiences and the assessment valuation is how we learn from those experiences and what we learn from those experiences? And from that learning, we decide what to want next.

Hunter Hastings:

So one of the ways I interpret that, tell me if you agree is that the consumer’s got a lot of effort here, got a lot of work to do. You say in the paper they have a job to do. It’s a discovery task and an innovation task. And you specifically say the role of value discovery and value innovation is the consumers, the entrepreneur can’t do it, because they can’t observe this evaluation.

Hunter Hastings:

So we’re giving work to the consumer, where I’m going with that is one of the implications for entrepreneurs in delivering convenience is think about that work. How hard does the consumer have to work to evaluate your offering and make it easier for them? Is that an okay way to translate what you’ve said here in the paper?

Per Bylund:

Yeah, I think so. That’s a good way of putting it. I mean, since we are arguing that value is completely on the consumer side and that value is the experience. And therefore that there is some certainty in the value for the consumer too. So this consumer seeks to get the value out of things, but doesn’t necessarily can be wrong. It does mean that for the entrepreneur, what they need to do is in a sense offer something that is potentially of greater value for consumers than other entrepreneurs are offering.

Per Bylund:

What that means is also that entrepreneurs can only get to the point where they facilitate value for the consumer, but whether the consumer actually chooses it, whether the consumer actually gets value out of it, that is really beyond what they can do. So whenever they sell the product, which can facilitate value for the consumer, the entrepreneur is sort of done.

Per Bylund:

I mean, the entrepreneur can, of course, offer service and whatever support might be part of the product as well. But as soon as the consumer has and uses an experiences the product, the entrepreneur can’t really do anything about it. So what that means is, is that yeah, the discovery of what the actual value is on the consumer side, it also means that the consumer might discover and innovate and figure out new ways of using the product, or service and also sort of find completely different uses for what the entrepreneur has delivered. And I think we’ve seen that throughout history and in the economy all the time that it happens when entrepreneurs offer a new type of product or device that whoops, people did not use this as intended, or as the entrepreneur expected.

Per Bylund:

Instead, they used it in a very different way, which turns out that, that’s in a sense, it’s a different product. So the entrepreneur can learn from this value innovation that the consumer is really providing to the marketplace, in a sense.

Hunter Hastings:

So let me try and sum up the revolution on the consumer side. I think it’s really critical, this idea of the consumers got work to do they got a valuation work to do, they’ve got uncertainty they’ve got to overcome. And in my head, I contrast that with the famous Clayton Christensen claim, which is about objectified value, I think that the consumer has jobs to be done and the entrepreneur’s offering can do it.

Hunter Hastings:

And we’re saying the opposite here that the consumers doing the job. And the entrepreneur can really facilitate that. That’s I think, that’s my way of saying what the revolution is, you’re giving much more weight to the consumers role in value generation, than has been the case in the past.

Per Bylund:

Yeah, we’re sort of shifting the boundary between the entrepreneur and the consumer. Whereas traditionally, it’s been the case that the entrepreneur delivers the product, which has the value, and then the consumer just has to use it. And then of course, it’s some weird psychological thing going on whether the person is satisfied or not. And there’s plenty of, I guess, space for the entrepreneur to trick the consumer. And the disappointment is sort of the entrepreneurs fault, whereas the implication of our new boundary between where the distinction between where value happens and where it’s facilitated means that there can be plenty of disappointment in a good or service on the consumer side completely.

Per Bylund:

So the consumer has made a mistake in expecting to get certain value out of a product, but didn’t, there was nothing wrong with the product, the product was exactly as described, but the consumer made an error. So the entrepreneur is not at fault. But of course, it might mean that the consumer is no longer trusting the entrepreneur, and will not buy anything more from the entrepreneur and what have you.

Per Bylund:

And I think what it also does is, it recognizes the larger role of the consumer. What it also means is that the entrepreneur becomes more of a servant of the consumer than was the case before. That, instead of being the guys in traditional sort of entrepreneurship, where you figure out a product, you produce a product, and then you just take it to market and then consumers get to buy it.

Per Bylund:

Instead, it’s your problem as an entrepreneur to figure out what could cause a valuable experience for the consumer, of course in competition with what other entrepreneurs are offering. And then make sure to continue and follow up and help the consumer through through the use of the product and make sure that the consumer gets a valuable experience out of it, which is much harder than it sounds.

Per Bylund:

But what it does is points out that the entrepreneur is sort of in the hands of the consumer, whether the entrepreneur’s successful. It depends on how much he or she helps the consumer to get a valuable experience.

Hunter Hastings:

Yeah, so let’s focus on the entrepreneur side now, we flip to that. One of the phrases I picked up from the paper that really brought it home for me is that what the entrepreneur is doing is producing the means for consumers to use for their desired satisfaction.

Hunter Hastings:

So that’s a very creative way to think about the role of business, I think. You’re producing the means but you have no control over how the consumer uses those means. So all you’ve got is watching, observing and monitoring what the consumer is doing, is that a good way to say it Mark?

Mark Packard:

Yeah, it’s a bit of a paradigm shift in the way we think about business. Again, we’ve shied away from this language of value creation, because value emerges in the experience of consumers. And this means that value isn’t created by businesses, right? The experience might be created by a business, but the value emerges out of the experience. And honestly, even that’s not entirely accurate, because really, it’s consumers who consume, right? It’s consumers who are actually creating the experience.

Mark Packard:

So what businesses do is really just facilitate the opportunity for that experience for consumers. So what we say is and I think this is much more accurate, is that businesses facilitate value experiences that are expected to benefit consumers. And that’s a very different way of thinking about what business’s role is, we’re providing the means, the resources, the tools.

Mark Packard:

And some businesses are experienced businesses, they actually create the experiential environment for the consumer to experience that thing. But it’s the experience that really, ultimately matters.

Per Bylund:

So if I may add to that, I mean, we see some of the errors that come from seeing what the entrepreneur does as value creation. We see those in policy, which are, in a sense, disastrous policy propositions, where a producer of a thing is going to be held accountable for what the consumer does with the thing. That doesn’t make any sense at all when you recognize that no consumers can innovate, they can figure out whatever they feel like and have whatever experience they feel like for that good, whatever it is.

Per Bylund:

So the producer has no influence really over what the consumer does with a product, which is pretty obvious for anyone running a business that when you have made the sale well, if they resort to throwing the tomatoes they bought on people, instead of eating them well you can’t really do anything about that at all.

Per Bylund:

I mean, if you sell hammers, they’re intended to be used in construction work or what have you. Well, someone takes the hammer and bashes someone’s head in, that’s not the intention. But it’s sort of an innovation on the consumer side, not very productive one, but still. So holding producers responsible for what someone might do with a thing. It completely misunderstands what is going on here.

Per Bylund:

And it completely… In a sense it handicaps and undermines the position of any entrepreneur that whatever someone produces, can be used for something terrible, potentially, and something beautiful as well. But whatever the consumer chooses to do with it, it’s out of your control. So you can only try to make it valuable for a consumer, but you can’t really change the consumer’s behavior with the thing, how they use it, and so forth.

Per Bylund:

So I think producers make this error too, not only policymakers, but trying to steer users to use products in a certain way. An example of this would be Apple, for instance, where very often in Apple products, you can use it in one way, but you can’t really change it a whole lot. So unless you use the computer or the tablet, or what have you, the way that Steve Jobs intended and thought was a good way of using it, it’s kind of be a mess trying to use it.

Per Bylund:

And that sort of steering, it has the benefit of simplifying the product, and maybe simplifying the message. But it can also reduce the value that the consumer gets out of it and you can even make the value pretty much zero.

Mark Packard:

I was talking to my parents just the other day about WD-40 and all the things that WD-40 can do. And you know the story of WD-40 is that it was designed for aeronautical equipment, it was to prevent rust on aeronautical machines. But it is a huge product and a huge success because some of those employees took it home and started using it in different ways that it wasn’t originally intended for.

Mark Packard:

And yeah, let your consumers explore and try things with your product and see what they come up with because they can come up potentially with much more valuable uses for what you think it should do than what you think it should do. So, that’s a good point Per.

Hunter Hastings:

It’s the essence of what Professor [Kihani 00:30:44] called a couple of weeks ago, generativity, if you are unfiltered in what you let the consumer do, you’ll be unconstrained in the innovation that comes out the other side. So there’s a exponential potential there.

Hunter Hastings:

So let’s go back to what the entrepreneur can do, they can initiate a value proposition, “Hey, here’s something that I think will serve as the means to you, Mr. and Mrs. Consumer to fulfill your want.” And the wants today and wants tomorrow because of production taking time. And then they can monitor the consumers value experience and get some feedback from that, is that how we define what the entrepreneur can do?

Per Bylund:

Sure, why not? I mean, in a sense, they have to forecast or predict or imagine what could be of value to consumers and provide them with the means. And then seek whatever means of feedback there are in order to learn and just like we talked about, with WD-40, is a great example, that sometimes consumers use it in a much, much more valuable way than you had anticipated. Well, then it makes sense for you to follow up and try to figure out how they’re using it. And you can learn about your product’s actual value, by having a close relationship with the consumer.

Per Bylund:

So it’s not about selling something and then just turning your back and moving on. So any product in a sense, you can learn about the consumer experience. And you can have a relationship with consumers. And thereby realize how you can make the experience more valuable for consumers, maybe you can make a small tweak here and there. And that would facilitate more value for your existing customers or maybe you can make it valuable to a whole new range of customers.

Per Bylund:

I think it’s a little strange to assume that the entrepreneur can figure all this out to begin with. So when we talked about before that you should set place the value first and then the values determines the price that you might be able to charge for the product. And then your role as the entrepreneur is to choose the cost structure that can offer your profit given that your estimation of the price is correct.

Per Bylund:

Well, this goes beyond placing the sale that you can learn and you can continue to develop the product using the consumer’s experience and learning from the consumer how your product is actually valuable. And thereby you can improve your chances.

Per Bylund:

So I think a lot of modern companies recently anyway have had sort of adopted this model without, I guess, knowing exactly why. I mean they probably don’t have a value theory that they’re following. But having like panels of customers, providing feedback and looking at online reviews and things like that, in order to learn more. What did we do, right? What did we do wrong? Where’s the value add in a sense to this experience of our product?

Per Bylund:

And how can we help the consumer realize more value in using and experiencing what we have to offer? And there’s of course a lot you can learn. So you have to be open for that. And especially if you have a new product, it’s not easy to figure out exactly how people might use the product.

Hunter Hastings:

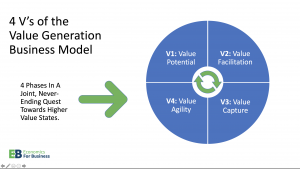

As we try to compose what we’re calling the Austrian business model, I think of it as three V’s and we’ve just covered I think the third one. So I call them value understanding, that’s what you two have been talking about all day, understanding what value is, value facilitation we’ve discussed that in depth. And the third term which might not be the right word, but is the right ideas, value agility, I.E. the agility to monitor the experience, take the feedback, make sure adjustments, take it back, see what happens next, continuous change and improvement. So I’m going to call that value agility.

Mark Packard:

Well, that’s also the on the entrepreneur side. The agility is on the entrepreneur side. But what you’re looking at is really an enhancement of the value experience for the consumer. So you have to be agile to respond to those things, but also to sort of suck in that information that might or might not be available.

Hunter Hastings:

Yep. The three V’s is a business model for the entrepreneurs, hopefully, as we perfect it. So another phrase you used in the paper, I think, Mark we’ll ask you this is that in all of this, the entrepreneur can never know. Never know what the value outcome will be. So just take us there, how does the entrepreneur act in that situation?

Mark Packard:

Yeah, Per was kind of talking about this. But when you think about it in this way that we’ve been discussing, the uncertainties and the difficulties of business become a lot more apparent, and you start to see how business isn’t just production and sales, it’s really about providing consumers with the best means to achieve the best experiences.

Mark Packard:

But again, everyone is different, and their value experiences must be unique. Because we’re also different, and we experience things differently. And this means that consumers will, over their lives, end up with very different value learning processes and conclusions and that means different preferences.

Mark Packard:

And so even if you could know for sure that your product would be subjectively beneficial to someone, it doesn’t really matter what you think, it matters what they think. And so you can’t ever know, what the value outcome will be. But you’re you’re doing the best you can with this uncertain future, with what you have, and you’re making your product as beneficial as it can be. And I’m doing some work on kind of these narratives, we’re painting a picture, we’re telling a story that helps consumers understand how what we’re doing, what I’m doing as an entrepreneur, would help you. And that’s about the best we can do.

Hunter Hastings:

So in the paper, you find another fascinating and important route for pursuing this idea of subjective value and entrepreneurship, and that is the entrepreneurs choice itself to be an entrepreneur, to act entrepreneurially. And you say that they’re not looking for dollars and cents in profit exclusively, there are non monetary rewards and satisfactions from facilitating the satisfactions of others. So I think Per maybe that’s developing a little bit more what Mark said, but take us there, the entrepreneurial choice and it’s subjectivity.

Per Bylund:

Sure. It’s really the same value theory that we’re saying that well, value is the experience you get from something, which obviously is not the dollars and cents that you get as profits, because your experience of that is something else, either, it could be the prestige of becoming rich, or it could be the prestige of being an entrepreneur, but it can also be the getting the means to consume something for yourself. Or it could be just simply being your own boss, or it could be all of these at the same time.

Per Bylund:

So the question for the entrepreneurs is really, why am I doing this, which is not necessarily even related to profit. Obviously, you would need to cover your costs and breakeven in order to continue running the business unless you’re Bill Gates or something. But other than that, I mean, why are you doing it. Most entrepreneurs are probably not in business for just reaping in cash and getting rich. I mean, the data shows pretty clearly that starting a business, it’s not a super way to get rich because entrepreneurs they typically make a little less as entrepreneurs than they make as employees, if you can compare the situations.

Per Bylund:

So it’s the same situation as for the consumer, but the value that you get of something is the experience and how you treasure and how the experience satisfies whatever wants you might have. So it’s wrong to as we often do study entrepreneurship in terms of the profits they make and thinking in terms of just the dollars and cents that you get in and that you sort of put in your own pocket.

Per Bylund:

Because that’s probably not what drives the entrepreneur just like it’s not what drives the consumer, whereas we think it’s pretty obvious for the consumer because the consumer pays cash in order to get the experience. But I mean, the entrepreneur does the same thing. It really is a subjective value world. And the analysis of it should then be subjective value analysis as well.

Hunter Hastings:

So in the paper, I’ve got some language here that I need you to unpack for us, you describe that entrepreneurship as a choice. It’s a contingent voluntary action of goal driven actors. I think I can translate that. And then Mark, you say the entrepreneurs uncertainty is not epistemic, which I take to mean knowledge constraints, which we’ve talked about a lot on this podcast. It’s aleatory if I pronounced that right, it’s randomness. So can you explain those two terms about uncertainty for our listeners in business language? How do I deal with aleatory uncertainty?

Mark Packard:

Yeah, I pronounce it aleatory, but I’m not quite sure what the right… It’s a Latin term. But the difference between what we call epistemic uncertainty versus aleatory uncertainty is epistemic uncertainties are ignorance based, they are things that you can know if you collect enough information. If I toss a die, there’s a one in six chance it’s going to come up a six.

Mark Packard:

But if I knew exactly how that die was cast and all the factors and stuff, it is possible for me to predict exactly what face that, that die is going to land face up. But there are other types of uncertainties that there is just indeterminate, it’s not random, it’s not even happened yet. Right? It hasn’t been determined, like other people’s choices.

Mark Packard:

A lot of things happen based on what other people choose to do. And they haven’t made those choices yet. So we can’t predict those future outcomes, we are waiting for people, including ourselves to make those choices. And so the outcome in that sense is just inherently unpredictable. Doesn’t matter how much data we collect. And so I get a little frustrated when B-schools and just industry experts talk about the promise of say big data, and artificial intelligence in predicting consumers and all this stuff.

Mark Packard:

Because consumers are people, they’re not going to be… They’re not automatons, they’re not computers, they’re not predictable in that sense. We don’t know what people will value in the future. We have to predict it as entrepreneurs, as business people, we have to predict it. But we can’t predict just by collecting more market data. Market research is important. We need to understand our customers and consumers.

Mark Packard:

But we can’t kind of jump in assuming this conclusion is right, we understand our consumers. And so this is going to work, we have to accept the fact that people are unpredictable, that they can change their minds, that they can surprise us. And going in with that mindset allows us to be more adaptive, more agile, as you were saying, and adapt to what they find and what they discover over time. And we can learn from them as we learn ourselves, and that makes this learning process both two-sided. The consumers are learning and we are learning with them.

Hunter Hastings:

In fact, that’s a beautiful phrase that you two had in the paper, you say entrepreneurship is the two-sided navigation of radical value uncertainty. So both sides have radical value uncertainty. In the never ending quest towards higher value states. So that gave me a good feel for the dynamics of it. And it’s a new definition of what entrepreneurs do.

Hunter Hastings:

And if I can pick up on another phrase and Per maybe you can take as long as… It’s a mental journey or process. A series of imaginings, judgments and learning over time. So tell us about that. It’s a journey.

Per Bylund:

Well, it truly is a journey, and in a sense it’s a learning process where you’re trying to figure out and you’re responding to whatever feedback and whatever information that you might come across along the way. The problem of course, is that everything requires your interpretation and your imagination of what it might mean. It’s definitely not as easy as simply looking at statistics and then picking whatever is the most significant variable or something like that.

Per Bylund:

Entrepreneurship is nothing like that. And it’s funny that Mark mentioned that such statistical and big data analysis. I wrote an article before, I think it was on mises.org. Commenting on the Bing search engine, where they had an attempt to using big data to predict who would win in sports games, football and basketball, and ice hockey and what have you.

Per Bylund:

And I looked at some of those results. And it turns out that pretty much consistently they were two thirds right. And then they were talking about a sport where you know a lot of statistics about the players, you know exactly the rules, you know how much time they have, you know exactly their positions, you know the rules, they are pretty obvious, they’re explicit to all the rules. So, it doesn’t actually give you a lot of space for unknowns, because everything is already structured, and it’s clear, still big data could only predict two thirds of the actual outcomes.

Per Bylund:

Even given the historic data on say if the team is having a good streak, or whatever, even with this information, they still couldn’t get it right. And then, of course, trying to use big data to predict what will people value in the future, I mean that’s impossible, what you can do is potentially exclude things that are probably not relevant or exclude ways or routes that are not going to be very helpful.

Per Bylund:

But you still have to base it in your own imagination of what will be the case of your imagination of how consumers will use your product and how they will cherish the experience that they get, sort of empathize with them, placing yourself in their shoes. And of course, learn along the way and learning along the way that journey as we said before, it doesn’t end with placing the sale, it continues, because that’s where you can start to learn about your product, and how consumers actually experience the product when they’re using it.

Hunter Hastings:

So let me wrap up there with a question that’s pertinent for our economics or business project. And you’ve given everything that you’ve just explained and elucidated so much. We’re trying to facilitate more successful entrepreneurship, meaning you can better help consumers to get satisfaction, to experience value, we think of it as a GPS to use your journey metaphor, which is given where we want to go more satisfied consumers.

Hunter Hastings:

Here’s where I am right now. And here are some things you can do to make that journey more accurate and more successful. So is that doable? And the way you’ve just described it? Can we facilitate more successful entrepreneurship? Better two-sided navigation of the process?

Per Bylund:

Yeah, of course. I mean, what we’re talking about here is really facilitating the facilitators of value. And I think, getting your mind in the right place, thinking about these things in the right way. That’s the place to start. And unfortunately, not only do many entrepreneurs, not realize these things, and of course, they don’t have to read scholarly papers or anything like that, but they need to have a proper thinking about how the world works and what they’re actually offering that they’re not selling a valuable product, they’re offering a product that can facilitate value for consumers, which is different.

Per Bylund:

And unfortunately, many business schools are teaching this in the wrong way and using objectivist language and we had a podcast before when we talked about how they’re using analogies from military conquest and things like that. And that’s terrible, that’s not only misunderstanding value, that’s completely flipping everything upside down and putting it on their head because it’s not the case that you’re conquering a market and you’re subduing the consumer, you’re doing exactly the other way around.

Per Bylund:

You’re trying to figure out how to serve them the best way possible. That doesn’t make you a king or a conqueror. It makes you a servant in a sense, and you benefit and serve yourself by serving others. The consumer really is sovereign in the marketplace.

Hunter Hastings:

Mark I’m going to leave you with the last word on facilitating entrepreneurship.

Mark Packard:

I totally agree with Per. I mean, I think one of the tasks or goals of the Economics For Business program and project is to get business people and entrepreneurs to understand economics in a fundamental way. And as Per was saying, the current paradigm in social science, including management and entrepreneurship researches is objectivist view, where you just kind of look at these various factors A, B, and C and see what kind of effects, statistical effect it has on D.

Mark Packard:

And based on that analysis, they say, “You should do A or C, and that’s just not very helpful if you’re an entrepreneur, because you don’t really understand the mechanisms of why. But Austrian economics, this deep understanding of how economics actually works, gives us that why and that helps you to navigate the uncertainties, the dynamics of economic change and process. And that’ll help you a whole lot moving forward.

Hunter Hastings:

Well, I want to thank you both for the incredible work that you do throughout your research and your theorizing, this paper is a particular breakthrough I think. And it’s certainly facilitated a good experience for me, and I’ll do what I can working with you too and everybody else at the Mises Institute to get more and more people to appreciate the implications of it, because I think they’re colossal.

Hunter Hastings:

So thank you both for today. And thank you for the ongoing work and we’ll continue to try to make this as useful as possible for everybody out there who’s listening. Thank you.

Mark Packard:

Thanks Hunter.

Per Bylund:

Thank you.