31. Per Bylund on Big Data vs. Big Ideas

Wouldn’t it be nice to predict the future? It’s tempting to reach for the analytical tools and big data sets that are newly available and for which big claims are made regarding their predictive capabilities. For entrepreneurs, small businesses and corporate innovation teams, rich qualitative data are far more relevant and collecting these data is far more productive. By this we mean talking to customers and potential customers, observing behaviors rather than collecting clickstream data, and immersing yourself in the unpredictable subjectivity of the consumer.

In this week’s Economics For Entrepreneurs podcast, Dr. Per Bylund analyzes what big data can and can’t do for entrepreneurs and the innovation process, and explains how qualitative data can generate big ideas for the future.

Key Takeaways and Actionable Insights

Predictive analytics can’t predict! That was Dr. Per Bylund’s provocative introduction to our discussion of the uses and drawbacks of big data in the context of the entrepreneurial mission.

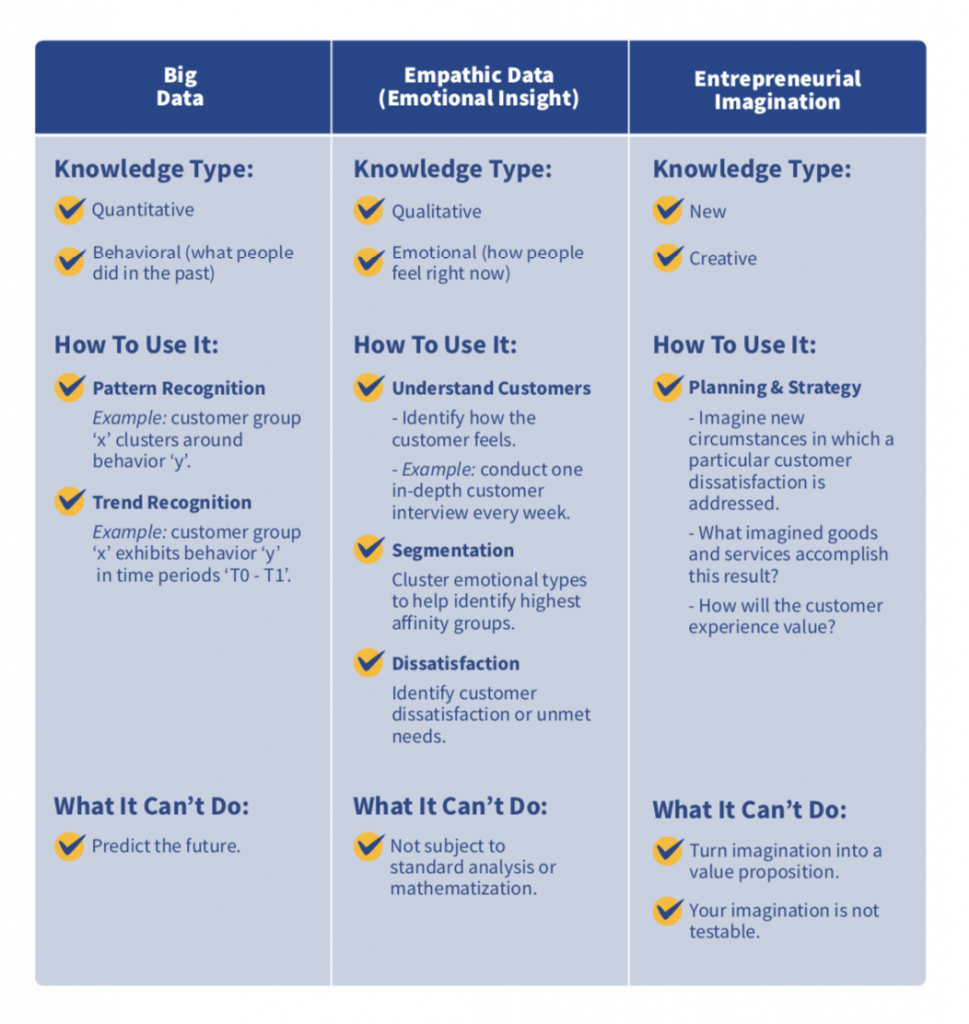

The claims made on behalf of the analytical powers of big data may be exaggerated, and entrepreneurs should learn what they can and can not expect from the application of big data analytics to business. Otherwise there is the chance of both error and wasted spending on the tools of business intelligence. It’s important to distinguish between the different roles of multiple data types.

Pattern recognition is not prediction. Dr Bylund contrasted what Big Data can and can’t do for entrepreneurs. He used an example of analytics predicting the outcomes of future NFL games. Here there are large sets of historical data on players, teams, plays and previous outcomes. There are limited potential outcomes (e.g. one team will win the game – there is no third team that will unexpectedly turn up to change the range of possible outcomes). The predictive analytics got the outcome right about 75% of the time. In a world of more open-ended results (e.g. predicting the outcome of a multi-team tournament), big data could be expected to be right fewer times. There is danger in over-reliance on the law of large numbers and tendencies like reversion to the mean. Pattern recognition from historical data sets (which is what big data does well) is not prediction.

In fact, in the world of economics and entrepreneurship, there is no prediction. Entrepreneurs deal with social phenomena that emerge from individuals’ actions and interactions, across billions and trillions of instances. Entrepreneurial outcomes depend on how people act, and how they act depends on their feelings, how they see the world (subjectivism) and what they feel like doing. We can’t know or predict that. There may be some general rules that apply in many cases (for example, raising prices rapidly and significantly in a competitive market will, all other things being equal, result in a reduced unit volume of sales). But those rules don’t predict the decisions of specific individuals in specific cases.

Mainstream economists and central planners long for a mechanistic world: turn a dial, get a result. But this approach is not valid. In the economy or any market, all variables are dependent on all other variables. Everything affects everything. The consequences of any action – like central bank interest rate tinkering – affect different people in different ways, and whoever is affected first or last will experience different consequences and react in different ways.

The core of the issue is that human behavior is unpredictable. Subjective choices can’t be predicted.

Prediction implies precision, and that’s not available.

Yet the entrepreneur must deal with the future. The entrepreneur seeks to produce a good or a service that consumers will consider valuable at some point in the future. Even if they tell you today that they will value your offering in the future, they may change their minds.

Is there any contribution that big data can make, any help that it can offer? We discussed these areas:

- It’s hard to know what people might want in the future. But it might be possible to identify what specific people will not want, based on their past behaviors. Data can show you which purchases cluster together, and which don’t. Beef purchasers may also buy red wine. Vegans won’t buy beef. Facebook and other ad targeting tools (which use big data effectively) can help you avoid marketing beef to vegans or pasta to keto diet followers.

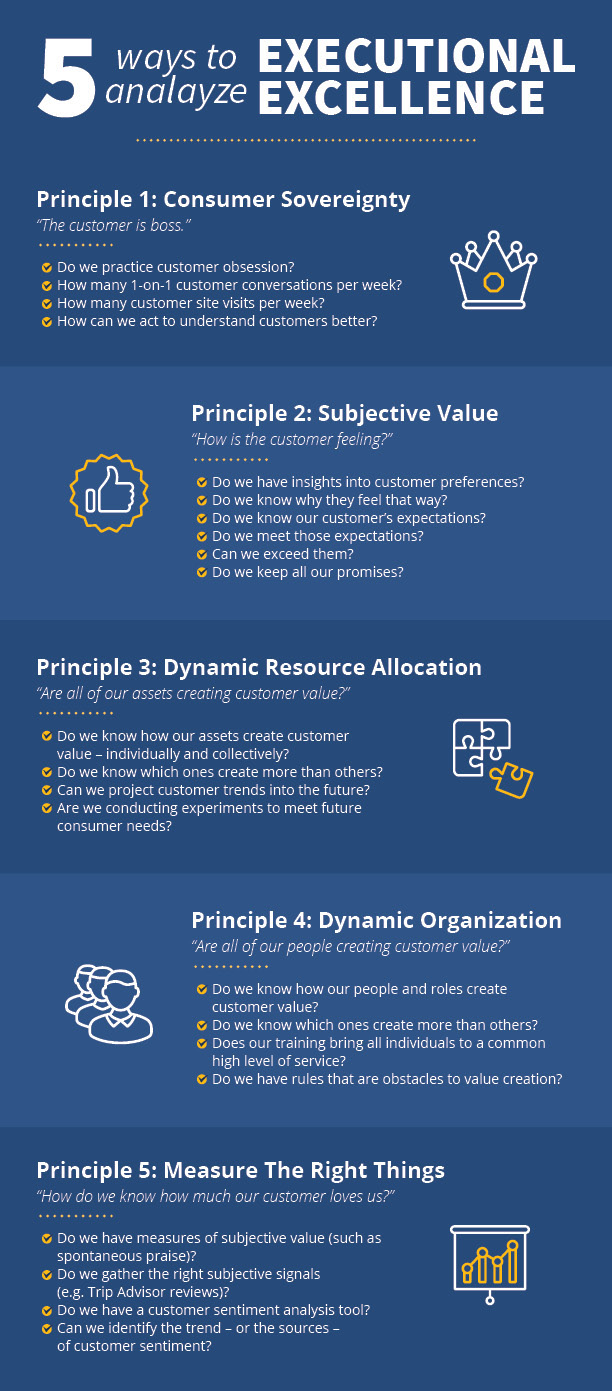

- Data can sometimes detect dissatisfactions, which are the universal raw material for entrepreneurs. Analysis of sentiments expressed in reviews can guide you in the right direction. Writing a negative review on Yelp or Trip Advisor is both a behavior and an expression of sentiment and data analytics can detect patterns here. But Dr.Bylund advises us that it can only provide a guide – there is no substitute for talking directly to consumers, human to human.

- Data can help with segmentation. If you want to better understand a geographical market segment or a demographic segment or a behavioral segment, there are lots of data that can detect the differences between segments, and this can help you with targeting of communications (but not necessarily with the message).

- Quantitative data can be combined with qualitative data to sharpen insights. Dr. Smita Bakshi, in our episode #24 described how analysis of student performance data (50% of computer science students don’t complete their first-year course) combined with personal discussions with students in class, delivered an empathic understanding of their struggles, from which her team developed a winning interactive learning tool for computer programming languages.

Sometimes an entrepreneur can skip the big data analytics, but never the empathic diagnosis. Entrepreneurship consists of understanding the mind of the consumer and understanding the economics of the marketplace. Where the market is heading and what will be in consumers’ minds in the future are more the realm of judgement than analytics.

Entrepreneurs behave differently than dig data-driven large corporates. They think harder about the customer, they study human motivation, they utilize the rich qualitative data that comes from talking to customers, and they concentrate their capital and resources on developing and extrapolating their customer understanding. They uncover subjective value – the value that only exists in the mind of the consumer. Imagination is the key to the future. Entrepreneurs try to succeed in bringing about that imagined future. Big data might help them avoid mistakes, but it’s impossible to rely on the past to produce the future.

DOWNLOAD

Download Our Big Data vs. Big Ideas PDF (129 KB)