56. Steven Phelan on Building Trust and Exerting Control in Collaborative Business Relationships

All business relationships have downside risk: your counterparty / partner / vendor / customer / investor may not perform as you expect or require. In today’s interconnected economy, more and more elements of your business model are provided by relationship partners. It’s wise to recognize downside risk potential and to know how to mitigate it.

Key Takeaways and Actionable Insights

There are two relevant types of risk to consider:

- Relational risk, sometimes thought of as character risk: that your business partner may not perform as you’ve agreed to because they are taking advantage of you in some way.

- Performance risk, sometimes thought of as competence risk: your business partner intends to perform as agreed, but is incapable of doing so for competence, capability or resource reasons.

For entrepreneurs, there are two levers for risk mitigation: trust and control.

Trust includes Goodwill Trust and Competence Trust — trusting your partner’s character and capabilities respectively.

Control includes output control, behavior control and social control.

Output control is generally thought of as setting measurable targets and monitoring performance relative to those targets. Did your partner meet the agreed-to sales targets in dollars or units? If they did not, they are not performing. This is a means of performance or output control.

Behavioral control focuses not on output but on behavioral inputs: did all the team members check in at 8am this morning as agreed? There is no guarantee that the desired behavior will lead to the desired output performance, but you think they are correlated and the behavioral commitment sends a signal of positive intent.

Social control is thought of as shared values and norms. If the collaborating teams or individuals have shared values and a highly-networked clan-like environment, they are more likely to have shared commitment to the goal.

Trust is much more positive for business relationships than control.

When people in business relationships exhibit integrity and good character, and perceive it and experience it in their collaborators, there is less need for output controls and behavioral controls. They’ll do the right thing without those controls in place.

From an economic point of view, trust reduces transaction costs — the cost of making sure that people are following agreements and doing what is expected of them.

Trust is a business competency.

Trust holds relationships together. For this reason, it is a business competency. It’s the kind of competency that fits well into the Austrian economics mindset: it’s a soft skill, not quantifiable, highly individualistic, with a significant moral component to it (doing the right thing).

Viewing trust as a business competency means that entrepreneurs are able to develop trust-building as a skill, one that can be reinforced and strengthened over time. It starts with an individual’s nature: you are someone who can be trusted. Such a nature attracts others who value it. Business speeds up, and runs more smoothly, with less need for high-litigation problem solving and more instances of viable handshake agreements. Start with your own character and seek to identify the same character type in those you deal with. There’s an element of Austrian subjectivism: there is no formula for “how I can trust someone”, but you can develop the skill over time, even learning from entrepreneurial error when you mistakenly trust someone who doesn’t deliver.

Trust is a value.

People want to feel trusted and seek relationships that feature trust. Trust is a business skill that’s as valuable to you as operational knowledge or financial expertise. Learn how to build and maintain trusted relationships with other stakeholders.

Trust is a resource.

Resource and competency are two sides of the same coin. Trust is a resource that fits into Austrian Capital Theory as an asset that generates revenue from customers. Think of relationship capital and social capital and the culture of the organization that generates trust as assets on the balance sheet, even if conventional accounting can not recognize them.

The 4 Cores Of Trust

In The Speed Of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything, Stephen M.R. Covey identified 4 cores of trust.

Integrity: Honesty — telling the truth and gaining credibility by doing so. Leaving no gap between what you say and what you do. Humility — being concerned about what is right and not just with being right. And the courage to do the right thing.

Intent: People judge you by your intent, which grows out of your character. If you “declare your intent” and your behaviors are consistent with your stated intent, people will trust you. Your motive is clear and honest, and your agenda is open.

Capabilities: Can you do what you say you intend to do? Do you exude confidence in your own capacity?

Results: What’s your track record? Do you take responsibility for results?

Integrity and Intent relate to character, capabilities and results relate to competence.

In a high trust relationship, everything speeds up. Trusting people give you the benefit of the doubt. Morale is high, people volunteer to go the extra mile, and they don’t resist changes you want to make. High trust liberates the relationship and its potential.

But don’t trust too much, or where it’s not justified.

In the long run, we all gain by trusting each other to give and not to take. But at the outset, you may not know if you are dealing with a taker or a giver. You should maintain a contingent element in your business relationships.

When you have many opportunities, you should be very intolerant of people who do not live up to their word. Do not be forgiving at all.

If you have fewer opportunities, maybe you have to be more tolerant of others doing the wrong thing and try to remedy the situation while maintaining the relationship. But giving people more than 2 or 3 chances to do the right thing is about the limit. Be willing to cut people off. Re-evaluate and measure the level of trust continuously. Be on guard especially at the earliest stages.

Trust-building Mechanisms

Trust in relationships is a business principle, and, as always, entrepreneurs need mechanisms to apply their principles effectively. Steve Phelan gave us the story of a large and successful General Contractor in the building industry. This GC put an enormous amount of time and effort into relationships with sub-contractors, so that there came to be tremendous trust between the parties. He would start them on small jobs, and gradually increase the size of the job in which they were invited to participate. At each escalation, the sub-contractor had the opportunity to prove that they could handle both the competence and character aspects of the relationship, as well as the capability and results aspects. Trust was built over time — a learning process for trust.

The same was true on the customer side. The General Contractor would decline to bid on very large jobs from a developer with whom he had not worked before. He would always start with a small commitment, and demonstrate mutual integrity and shared intent at that level, before proceeding to larger jobs.

Over time, as a result of this trust learning process, the General Contractor’s reputation and relationships became stronger and stronger, enabling smoother and more efficient operations in good times, and resiliency in downturns.

Summary

You can build trust in relationships and you can recover it. Don’t just think in terms of compliance, think about building a network of trust around you with customers, suppliers, employees, investors and partners. You can lower transaction costs and make your business run more efficiently. Make the investment to strengthen your capabilities in trust-building. Build a culture and a set of norms where people mange themselves and don’t have to be watched around the clock 24/7. Shape the organization you want to operate and live within for the rest of your life.

Free Downloads & Extras

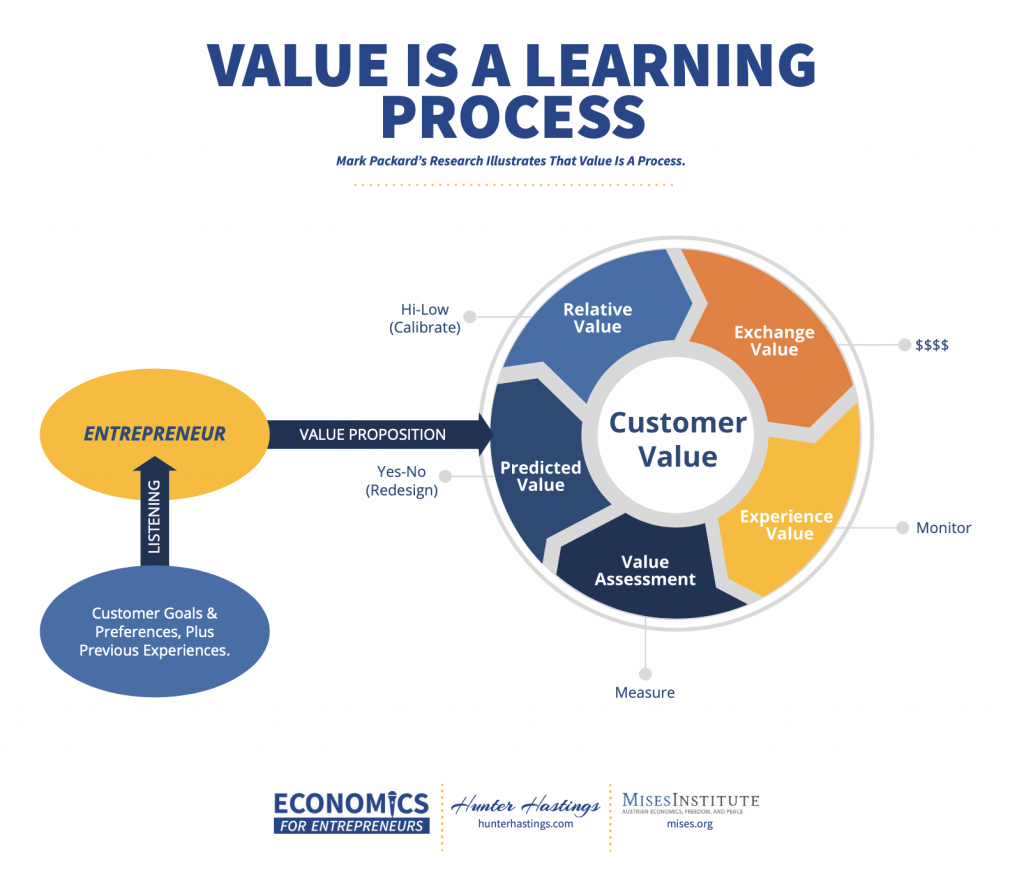

Tools of the Value Learning Process: Our Free E4E Knowledge Graphic

Understanding The Mind of The Customer: Our Free E-Book

Start Your Own Entrepreneurial Journey

Ready to put Austrian Economics knowledge from the podcast to work for your business? Start your own entrepreneurial journey.