Customers don’t have problems to solve. They have imagined futures that are better than today.

One view of how businesses succeed is that they solve the problems that people need solving. That’s the “jobs to be done” school of thought, popularized by Clayton Christensen and embraced by many others. This school of thought pictures people’s lives as being full of problems, and the role of entrepreneurship and innovation as fixing them.

Do consumers buy a subscription to Netflix because they have the problem of being bored or repulsed by alternative content? Do startup companies buy cloud services from AWS because they have a computing problem to solve? Does Mom buy frozen dinners to solve the problem of what to feed the kids?

No. It’s the wrong mental model – the wrong way to think about the demand side of economics and the role of businesses in our lives. The energy of economic growth derives not from the negativity of thinking about problems but the positivity of thinking about opportunities for betterment. The capitalist business system is powered by customers’ imaginations. They see the possibility of a better future, a set of circumstances that is different from and preferred to the current state. They imagine this desired state, not so much as a set of features, but as to how they will feel in it. Today’s circumstances may be fine, but there’s always that inner voice that thinks, “Things could be better.” When it’s really important, “Things that matter to me could be better.”

It’s purely an act of creativity. It’s what social scientists call “counterfactual”. People are imagining a future that doesn’t yet exist, yet they can conjure up the future feeling in their mind. There might not even be the possibility of it existing today, because it requires an innovation to bring it about. How brilliant is that? It’s the same level of imagination that Einstein employed to think about relativity and Niels Bohr used to think through quantum physics, when relativity and quantum theory didn’t yet exist.

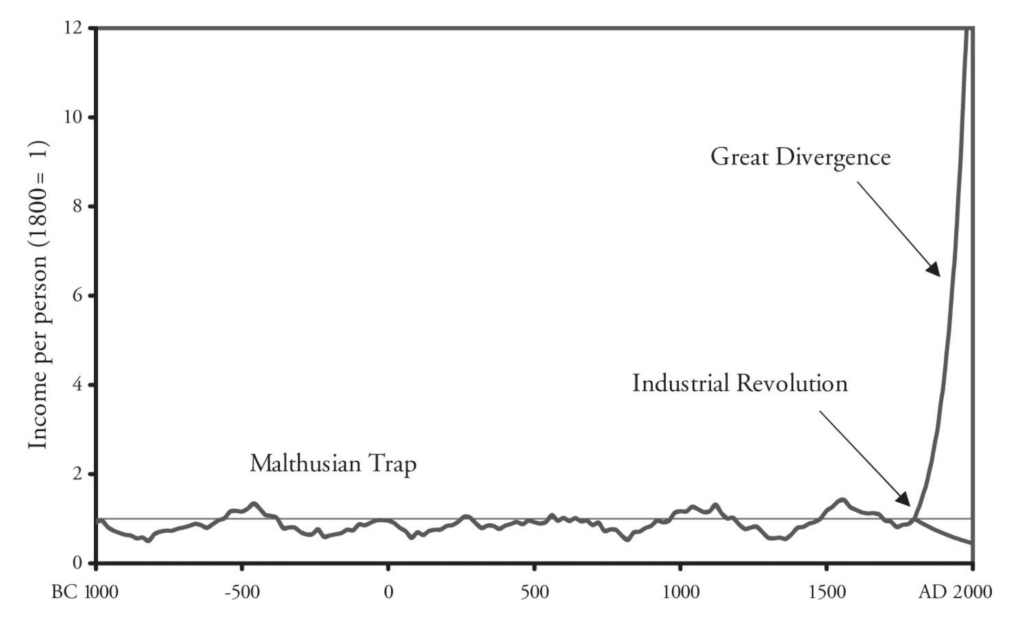

It is cognitive acts of counterfactual imagination that drive civilizational advance, the unrelenting seeking of human progress. And the same counterfactual imagination drives commercial innovation, from the iPhone to new flavors of breakfast cereal. Things could be better. Our phones could cease to be tethered so that we can talk on them while walking. They could cease to be clunky so that we can enjoy the elegance of design. They could help us do multiple tasks so that we can carry one device instead of many. Users didn’t invent these functions. Users made them possible by imagining the world as a better place – more convenient, more amenable to our preferences for convenience and speed and aesthetics. By being open to new value propositions, users bring new value into being.

The other face of the customer’s imagination of future value that’s better than today’s is entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship is the business function that turns the customer’s imagined future into commercial new reality. Entrepreneurship is the second stage of innovative genius, the stage that responds to the customer’s initiation. Entrepreneurship is the imagination of not just the future feeling of satisfaction that the customer feels, but also of the product or service or proposition that delivers the satisfaction. Entrepreneurial imagination becomes more and more substantive over time. It starts with an idea – “what if we were able to….” – that’s framed in an incentive: there could be a significant economic reward from the customer if we are successful in realizing the idea as a deliverable product or service. The process moves from idea to concept to some kind of early-stage artifact (the sketch on the back of a napkin) to prototype and MVP and test market. At every stage there’s a check-in with the customer who is imagining a better future: is this idea / concept / artifact / prototype / MVP aligned with your imagination? Is this what you were thinking? (Because, of course, they don’t “know” what they were thinking. What they had in mind was an abstract desired state. But when prompted with an artifact, they can respond – yes, that sorta/kinda points in the right direction. Such encouragement is sufficient to fuel the entrepreneurial development process.)

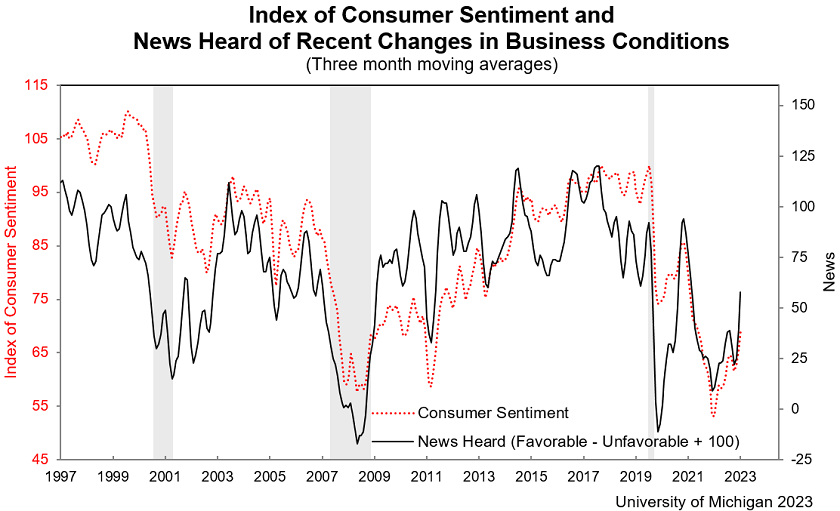

There’s an ultimate test of the alignment of the new value proposition with the imagined future state. It’s willingness to pay. If the customer is willing to make an exchange of something valuable to them – usually money or some derivative of money like a credit card payment, but also their time and effort – in return for the new product or service, it must, by definition, feel to them like it will bring about their imagined future state, or at least part of it, or, at the very least, provide a useful test of the viability of reaching that desired state through commerce.

People buy Tesla EV’s. Businesses buy AWS cloud computing services and harness Microsoft’s AI tools to help them succeed. These are all innovations that stimulate the customer’s imagination of a better world – an emissions-free transportation system that counters the trend towards climate change; a world of easy access for all businesses to the most advanced and robust computing power; a world of new learning and experimentation. These are all imagined first by customers – “these things that matter to me could be better” – and then by entrepreneurs in response. It’s not a linear progression, of course. Perhaps the first act of imagination that ultimately led to EV’s was the thought that air pollution from tailpipe emissions is unpleasant. That meme becomes a vector in a complex system where EV’s emerge from an unfathomable number of interactions and consequences and further interactions and new experiments and news cycles and conferences and scientific advances. We can’t untangle it. Reductionism no longer applies. There’s no cause and effect. But EV’s wouldn’t happen without customers imagining a better world in the future.